A Serene Garden Sanctuary

April 6, 2003By LINDA YANG

WITH my 95-year-old mother in tow, plus the guy she callsher "younger boyfriend" (he's 93), I wasn't sure we wouldall manage the seven-eighths-of-a-mile stroll through theJapanese garden at the Morikami Museum in Delray Beach,Fla. But knowing I can jog a 12-minute mile, I planted themon the dining terrace overlooking the lake, pointed them inthe direction of an exquisitely pruned gumbo limbo tree,and said "I'll be back in under 15 minutes!"

Thus began my introduction to the first of two new Floridalandscapes on my "must see" list: a tropical Japanesegarden and an orchid garden.

The 200-acre property that is now Morikami Park was aremarkable gift to Palm Beach County from George SukejiMorikami, who emigrated to the United States from Japan in1906 and died a wealthy landowner. He was the lastremaining and most successful member of the Yamato Colony,Japanese farmers who came to Florida for an agriculturalventure that ultimately failed. Shortly before his death in1976, he was quoted as saying he was giving his landbecause "America has been so good to me."

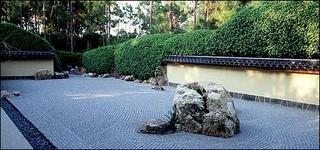

Fast-forward 27 years. The Morikami legacy has expandedfrom a small traditional pavilion that now houses exhibitschronicling the history of the colony to a spacious,elegant museum devoted to Japanese culture. And now thereis a new garden, opened in January 2001, where I foundblack olive trees pruned as if they were Japanese maples(which don't grow in the tropics), heard a shishi odoshi("deer chaser"), whose sound is made by a two-foot bamboostalk falling on a flat rock, and discovered aContemplation Pavilion, where a sign urges visitors to"listen with your eyes and see with your ears."

This 16-acre lakeside landscape is essentially a series ofcontrasting garden experiences inspired by various periodsin Japanese garden history, loosely linked by a meanderingpath. I began by traversing two small islands somewhattypical of the Heian period (9th through 12th centuries)connected by a zigzag bridge, stopping at the first benchto contemplate clattering bamboo stems and rustling whitepine needles.

This marriage of classic Japanese elements and tropicalFlorida plants is the work of Hoichi Kurisu, also aJapanese immigrant, and president of Kurisu International,a local landscape design firm. In partnership withRoy-Fisher Associates, Mr. Kurisu captured the essence of aJapanese garden - with its ever-changing reflections ofwater and sky, traditionally constructed bridges and gates,sound of water splashing on rocks - and tropical speciesthat appear absolutely at home in a Japanese gardensetting.

"A Japanese feeling is really achieved through thedetails," Mr. Kurisu explained. It comes from choosingappropriate species, pruning them artfully and developing"a harmonious relation between such elements as rocks andwater."

And so the garden includes Florida favorites like slashpine, podocarpus and strawberry guava trees sculptured toreveal the magical shape of their trunks and limbs. Thereis also a wall of fig trees, to help maintain the mood byblocking neighboring eyesores of the newly built homes inthis area just 15 minutes from Delray.

"Traditional Japanese gardens are mostly green," Mr. Kurisusaid, but "to add some awakening color there might be abright red cushion." Indeed, at surprise intervals, I wasawakened by powder-puff shrubs, known for the shock valueof their reddish blooms.

Rocks and moss, essentials in a traditional Japanesegarden, posed a special challenge, Mr. Kurisu said. "Ilooked at rocks in the Carolinas and Oregon, but they werethe wrong color - too gray for Florida." His solution waspink-hued granite carted in from Texas. "But moss, soeasily grown in Japan, is hard to nurture in tropical heatand sun," he added. "So I was delighted to find a bravelittle patch developing in a damp corner."

When pressed, Larry Rosensweig, the museum's director andresident visionary since 1976, admitted that his favoritespot was on the far side of the lake. I knew I'd found hisverdant retreat, with its orange jasmine and jacaranda,from his description of an "almost invisible long-leggedkotoji lantern and a special U-shaped stone that looks asif it's been there 10,000 years."

I agreed when he added: "This is a remarkable refuge - atrue oasis in the middle of crushing local development. Thenew Japanese gardens in particular - but really, the wholemuseum park - satisfies the soul in a most unique way."

Taking our leave of the Japanese gardens, my mother, theyounger boyfriend and I found the sign that marks the roadinto the American Orchid Society's International OrchidCenter, which I knew would be a very different experience.

A former goat farm, once also owned by Mr. Morikami, thisneighboring five-acre tract was recently bought by thesociety for its new headquarters, the first in its 82-yearhistory to be open to the general public. One of thelargest organizations devoted to a single plant group, theAmerican Orchid Society, which was founded in Boston, hasoften appeared too esoteric for ordinary mortals.

"But now," said Lee S. Cooke, the society's director ofnearly two decades, "we finally have a place where we canwarmly welcome everyone and introduce them to thisfascinating hobby."

Leaving my companions in the gift shop in the newMediterranean-style structure that also houses thesociety's offices, I headed out to the stone patio. Passingmassed plantings of annuals and perennials in brillianthues, I arrived at a large greenhouse.

Inside, I was stopped dead in my tracks by a 15-foot-high,multitiered waterfall draped in a floral fantasy of orchidsin every shape, size and color, from staid cattleyas ofcorsage fame to delightful oncidiums aptly known as"dancing ladies."

"Wedding parties love it here; it's a true Kodak moment" -Mr. Cooke's words echoed in my ear, and I marveled at thiswondrous if occasionally garish family of floweringspecies, the largest and most varied of any in the plantkingdom.

Returning outdoors past a formal garden, I ambled onto theundulating path that traverses the three-and-a-half-acrelandscape. Plantings along the path are organizedthematically by the various growing conditions that orchidsenjoy: jungle, native and water gardens.

Although donations of plants continue to arrive from allover the world, some 3,000 orchids are already tucked amongthe trees, shrubs and perennials that share theirpreference for the varied sites.

"In most gardens the flowers are all in the ground,"explained James B. Watson, the society's director ofpublications. "But many orchids are epiphytes, which meansthey perch on other plants." To replicate these growingconditions, the tree-perching orchids have been attached totheir favorite species by various means, including wire andliquid nails.

Among the many dozens of shrubs and trees transplanted hereto support the epiphytic orchids, I found a neem tree,southern magnolia and live oaks, sabal palms and screwpines. Along with their supporting role, these woody plantsprovide the garden with its strong structural outline.

And,thanks to the attaching methods, the trees and shrubs arealready festooned not only with clusters of bloomingorchids but also with some of the other epiphytes theyenjoy hanging out among. One staghorn fern had to be sixfeet across, and bromeliads flourished in countless shadesof orange and red.

Since education is a prime focus of this botanical garden,most of the plants are labeled: blue for exotics, green fornatives and frowny faces for endangered species. All aroundme, visitors were busily scribbling notes on variousspecies.

I stopped for a drink at the water cooler in the chickeehut, a local Seminole thatched-roof structure at the edgeof the Florida native garden, and realized my energy wasstarting to wane.

Returning to the gift shop, I saw that mymother and her friend were also ready to leave. After all,an early-bird dinner beckoned.

Visitor Information

The Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens and theInternational Orchid Center are neighbors in Delray Beach,Fla., an hour north of Miami, and half an hour south ofPalm Beach. On I-95 from the north, take the exit at LintonBoulevard (No. 51); from the south, take the exit at YamatoRoad (No. 48B). There is construction along I-95 in thisarea, so you may have to follow signs for detours. Thegardens share a single entry street, on the west side ofJog Road between Linton and Clint Moore Road, which iseasily missed if you're going too fast (though for reasonsI can't fathom their addresses differ). Both are wheelchairaccessible.

The Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens (Morikami Park),owned and operated by the Palm Beach County Department ofParks and Recreation, is at 4000 Morikami Park Road; (561)495-0233, http://www.morikami.org/. Open Tuesday through Sunday, 10a.m. to 5 p.m.; closed holidays; $9; ages 6 to 18, $6;under 6, free. The Cornell Cafe serves pan-Asian fare 11a.m. to 3 p.m., Tuesday through Sunday.

The International Orchid Center, headquarters of theAmerican Orchid Society, is at 16700 AOS Lane; (561)404-2000, http://www.orchidweb.org/. Open Tuesday through Sunday,10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Admission for the gardens: $7.

LINDA YANG is the author of four books on gardening,including "The City Gardener's Handbook" (Storey).

http://www.nytimes.com/2003/04/06/travel/06garden.html?ex=1050734059&ei=1&en=d2184f6e0f55014f

No comments:

Post a Comment