Today we have a guest post from Jonathan Bluestein on the history of Xingyiquan and Yiquan.

Xing Yi

and Yi Quan – The Real Story

By Jonathan Bluestein

Throughout the ages, many martial artists created their own fighting systems, usually based on older styles they have studied prior. Over the course of the 20th century, several of these teachers became famous and notable, due to a useful combination between their

Wang’s wonderful martial art

is nowadays considered a standalone style, and people discuss it as if its

qualities and essence are rather new. Yet in truth, Da Cheng Quan only one of

the latest evolutions in a long martial arts lineage, going back over 350

years. To gain a real understanding of what this art is about, how it came to

be and why it was created the way it did, we ought to therefore examine the

history of it predecessors, and the life of the man who created it.

In the picture: Wang Xiangzhai.

Whence it came

While Da Cheng Quan finds its

origins in the prominent, huge metropolis of Tianjin city, the source for its

gongfu was in the remote rural regions of Shanxi province. There, during the 17th

century, lived man whose name was Ji Longfeng, also known as Ji Jike (in

the years 1602-1683 or 1588-1682). He is the first individual to have practiced

what later Wang modified into Da Cheng Quan. The art likely existed before Ji

Longfeng in one form or another, but no prior record of it remains.

At that time, only one branch of the art existed, and was known as Xin-Yi Liu-He

Quan (Heart-Mind Six-Harmonies Fist). This martial art was and still is

primarily passed on within the Chinese Hui – a Muslim minority. Back in the

day, the Hui were not keen on sharing their art, which is why Xin Yi Liu He

Quan remained almost unknown until they started teaching it publicly several

decades ago.

In the following video –

very good explanations and demonstrations of traditional Xin Yi Liu He methods

and techniques:

A second evolution

In an unusual turn of events under these circumstances, Ji Longfeng’s student,

whose name was Cao Jiwu 曹繼武, taught the art to the Dai clan. These people the Dai were a

large family-based farming community, also from Shanxi. They mixed the Xin Yi

Liu He Quan they learned with their already existing eclectic knowledge of

martial arts, to create the system known as Dai style Liu He Xin Yi Quan. Like the Hui, they preferred to keep the art

to themselves.

Two generations passed. With their new skills and booming vegetable business,

the fame of the Dai clan grew. Of their abilities then heard one Li Luoneng 李洛能 (1807–1888),

a martial artist from Hebei province (a few hundred miles away). Back in the

day, it was often very difficult to locate a great master of the martial arts

and have him teach you. Li was seeking such men, and upon hearing of the great

Dai gongfu, sought instruction from them. This was challenging though, since Li

was a stranger from a faraway province, likely with a

different accent. He was not a family member, and neither did he have a formal

introduction of any sort from someone they knew. He then approached the

situation with great patience, and settled alongside the Dai clan, either

working for or with them in the vegetable business. Within a few years he was

able to convince the Dai family to teach him, and he gradually studied their

entire art.

In the picture: Late master

Wang Yinghai 王映海 -

famous exponent of Dai Xin Yi during the 20th century.

A documentary featuring

most of the Dai Xin Yi system:

Che style Xing Yi Quan

mixed with Dai Xin Yi methods – by master Yang Fansheng (the Xin Yi Dao

lineage):

The third wave

After finishing his studies with the Dai clan, ‘old farmer Li’ as he was called

left Taigu county, and wandered around the the Shanxi and Hebei provinces,

teaching many individuals. Li was a superb teacher, and quite a few of his

students gained mastery and fame with his art. But Li was in fact no longer

teaching exactly what he was learning with the Dai clan. He created a new style,

called Xing Yi Quan (Shape and Intention Fist). Because Li taught a lot of

people, and quite a few of them became serious teachers themselves across broad

geographic areas in two different provinces, his art became widespread and

famous across all of China, and is very common worldwide today.

Li did several things that distinguished his art. Firstly, he systematized it. Secondly, he added much content to it – many new methods. The original Xin Yi Liu He Quan is a very broad and diverse style, with a lot of techniques and forms. Dai Xin Yi is in comparison more concise and concentrated, with a smaller curriculum. Xing Yi was created based on the Five Fists and Twelve Animals – movements that existed before but underwent modifications, additions and re-classifications. There are also seven major additional, specific modifications that made Xing Yi stand out when compared to its predecessors:

Li did several things that distinguished his art. Firstly, he systematized it. Secondly, he added much content to it – many new methods. The original Xin Yi Liu He Quan is a very broad and diverse style, with a lot of techniques and forms. Dai Xin Yi is in comparison more concise and concentrated, with a smaller curriculum. Xing Yi was created based on the Five Fists and Twelve Animals – movements that existed before but underwent modifications, additions and re-classifications. There are also seven major additional, specific modifications that made Xing Yi stand out when compared to its predecessors:

1.

Zhan Zhuang, the

standing methods for developing Structure, Nei Gong and Dan Tian methods, were

now of the foremost importance for the training. These were not practiced in

Dai Xin Yi, and not nearly as important in Xin Yi Liu He. The main structure

and dan tian development method of the Dai clan, known as ‘Dun Hou Shi’

(Squatting Monkey posture), was omitted.

2.

The body

mechanics of the art were heavily influenced by the usage and wielding of the

Chinese spear. This weapon existed in the previous arts but did not affect

their empty-handed practice as much. Without training with the spear, it is

challenging to grasp the correct mechanics of Xing Yi Quan.

3.

San Ti Shi became

the most important training and fighting stance in the art, commonly replacing

Gong Bu. This stance barely existed in the practice of the previous styles, and

was used more commonly in transitioning between movements. Gong Bu remained in

practice and application to a lesser extent.

4.

A lot of the

intricate, internal body mechanics became smaller and hidden, while many external

movements became larger, compared with Dai Xin Yi.

5.

The Five Fists,

and especially Pi Quan, became the core of the art.

6.

Dai Xin Yi had 10

animal movements and methods. In Xing Yi there were now 12 of them. These were

extended to include more material from Li’s broader knowledge of the arts, and

some animals which were prior just a single combination or pattern became short

forms.

7.

The Si Ba (Four

Grasps) form of Dai Xin Yi, which was inherited (and modified) from Liu He Xin

Yi, disappeared from the art. Later, Li Luoneng’s students added many forms of

their own.

All of the changes noted

above, and several others, are key for defining Xing Yi Quan. They manifest in

all the subsequent branches of this art, of which there are many. Therefore, it

is safe to say that a sub-style of Xing Yi Quan ought to at least include

some variety of the Zhang Zhuang, usage of San Ti Shi, the Five Fists, Twelve

Animals, and Spear training. Later, many additional weapons and forms were

added to the art by Li Luoneng’s students, and these differ between schools.

Traditional Hebei-style Xing Yi Quan by master Yang Hai from Montreal (originally from Tianjin):

Traditional Hebei-style Xing Yi Quan by master Yang Hai from Montreal (originally from Tianjin):

Traditional Shanxi-style

Xing Yi Quan by various teachers from that province:

How the art came to

Wang Xiang Zhai

One of Li Luoneng’s most well-known students was Guo Yunshen. His name

spread far and wide, and he was good friends with other notable martial arts

masters of his day. Guo spent 3 years in prison for killing a man with his bare

hands. He used that time productively to hone his skills in the art, and came

out of prison as an even more formidable practitioner.

Wang Xiangzhai is claimed to

have been Guo’s disciple, but this is unlikely. The date of Guo’s death is

disputed. However, he either passed away either a short while before Wang was

born, or when Wang 13 (1898). Either way, Wang could not have studied seriously

with him. The version that assumes Guo was alive has Wang becoming his student

in 1893, when Wang was 8 years old. Xing Yi Quan is a very sophisticated and

advanced Internally-oriented system, and children do not possess the cognitive

ad physical requirements for learning such a style. This truth is so known and

obvious, that my own teachers rightfully refused to teach people under the age

of 18. Furthermore, some say that due to old age, Guo could no longer effective

demonstrate his art (though he was not very old, merely in his 60s). Also, it is acknowledged that Wang was a sickly child, was learning only method for improving his health in the beginning.

An even more contradictory version of the events is given to us by Wang Xuanjie, who was one of Wang Xiangzhai’s last disciples. In his book, Wang Xuanjie claimed that his teacher Wang Xiangzhai was born in 1890 (also supported by Xiangzhai’s daughter in a book from 1982), and that Wang Xiangzhai began studying with Guo Yunshen in 1904 (age 14). Yet the simple math easily shows, Guo Yunshen was resting underground for quite a while already in 1904 (depending on whom you ask, he either passed in 1898 or 1901).

The real teacher of Wang Xiangzhai had been a disciple of Guo Yunshen, whose

name was Li Bao (Li Zhenshan). It is possible that because of some technical or

cultural reasons, Wang was listed officially as Guo’s student instead of Li’s.

Such a thing happened commonly in traditional martial arts culture in China, and was also the norm in Guo's village. It

could also be that Wang later sought to associate himself with the more famous

and popular Guo. There are accounts by Wang’s disciple, a certain ‘Mr. Pan’,

that Wang indeed went through the Bai Shi ceremony in front of Guo’s grave

(meaning he was not really Guo’s disciple).

I am of the opinion that

because Wang began studying at young age and left for the army either as a

teenager or in his early 20s, he did not manage to study fully the complete

curriculum of the art. Wang himself told an interviewer that “he left his

teacher in 1907” - supposedly when he was 17 or 22 (though we know Guo actually passed away in 1898 or 1901, so he either left Li Bao age 17 / 22 or 'left' Guo Yunshen much earlier, as a young child, when Guo passed away). There is much evidence to this hypothesis I made (of partial instruction) later in Wang’s life. He never cares to mention the spear of Xing Yi, though it

is very important and was known to Guo, or any other weapons for that matter.

He never taught movement forms (taolu) beside, perhaps, some of the animal

forms (it should be noted that many animals variations are single movements and

combinations, not complete forms). The all-important Chicken Stepping of Xing

Yi, crucial for its fighting abilities, was not something Wang taught. In his

teachings there quite a few other things ‘missing’ as well from the original.

Yet because Wang later acknowledged to have changed the art, it is difficult to estimate what he never studied, and what he intentionally omitted. Only the end

result can be appreciated, and of that I shall write later.

In the picture: Xin Yi Liu He Quan master Jung Yung-Hwan (Korean

name). This typical Xin Yi Liu He posture has him standing in Gong Bu - a

stepping method now absent from Da Cheng Quan.

Wang goes travelling

A major problem we have with Wang’s life is that much of it is accounted for by himself. Wang was by no means an objective autobiographer however, and what he had written and said of himself in various articles and interviews was always clearly intended for self-promotion for him and his art – again making it difficult to judge truth from fiction.

After his short period in the military, we know that Wang went travelling across China, in his early 30s. He could have returned to study with Li Bao or other teachers of Xing Yi Quan, but opted not to do so. In fact, he seemed more eager to fight people than study from them at that point in his life. His articles proudly tell us that “he had fought many people across China, but was only matched in fighting by two and a half of them” (he was writing of three people, one of which he considered his equal – hence, “two and a half). He also said: "Those who understand me are wise people, those who condemn meshould sit alone in the still of night to listen to their hearts". In modern times, such arrogant expressions would have been met with much skepticism and uproar, and a fellow such as Wang would have subsequently been visited by a multitude of hoodlums looking to test him. I assume though that since Wang was a very skilled martial artist after all, he was willing to take such chances. But back in his day, during the first part of the 20th century, with the newspaper still being a ‘fresh’ medium, people very more gullible and willing to be fed such fantastic stories. He was not criticized openly then for his somewhat outrageous claims (some of which may have been true), and incredibly even today, many are willing to turn a blind eye to his bold writing style. He himself admits that, “to his dismay”, no teacher in his city of Beijing came to challenge (‘teach’) him following his public statements.

A major problem we have with Wang’s life is that much of it is accounted for by himself. Wang was by no means an objective autobiographer however, and what he had written and said of himself in various articles and interviews was always clearly intended for self-promotion for him and his art – again making it difficult to judge truth from fiction.

After his short period in the military, we know that Wang went travelling across China, in his early 30s. He could have returned to study with Li Bao or other teachers of Xing Yi Quan, but opted not to do so. In fact, he seemed more eager to fight people than study from them at that point in his life. His articles proudly tell us that “he had fought many people across China, but was only matched in fighting by two and a half of them” (he was writing of three people, one of which he considered his equal – hence, “two and a half). He also said: "Those who understand me are wise people, those who condemn meshould sit alone in the still of night to listen to their hearts". In modern times, such arrogant expressions would have been met with much skepticism and uproar, and a fellow such as Wang would have subsequently been visited by a multitude of hoodlums looking to test him. I assume though that since Wang was a very skilled martial artist after all, he was willing to take such chances. But back in his day, during the first part of the 20th century, with the newspaper still being a ‘fresh’ medium, people very more gullible and willing to be fed such fantastic stories. He was not criticized openly then for his somewhat outrageous claims (some of which may have been true), and incredibly even today, many are willing to turn a blind eye to his bold writing style. He himself admits that, “to his dismay”, no teacher in his city of Beijing came to challenge (‘teach’) him following his public statements.

So who were supposedly

(according to Wang) the people who defeated Wang Xiang Zhai? He wrote: "I have traveled across the country in

research, engaging over a thousand people in martial combat, there have been

only 2.5 people I could not defeat, namely Hunan's Xie Tie Fu, Fujian's Fang Yi

Zhuang and Shanghai's Wu Yi Hui”.

1.

Hunan's Xie Tie Fu 湖南解鐵夫 - In Hubei Province, Wang met Xie Tie Fu, known as

“the madman”, who was a practitioner of Xin Yi Chuan 心意拳. They fought 10 times and Wang was defeated each

time. Wang then suggested trying again using weapons, to which Xie replied,

“Weapons are only an extension of the body. You couldn’t defeat me without a

weapon, with a weapon the result will be the same.” Wang insisted and they

fought again, this time using staffs. Just as Xie predicted Wang again was

defeated. Ashamed he turned to leave when Xie said, “And what? You will

practice three years, and then come back to fight with me again? Better stay

with me. We can teach each other. I met many good fighters, but you are best of

them." Wang stayed and learned from Xie for over a year, and it was very

important for further development of Wang's martial art. When Wang was leaving,

Xie said that he was not sure about south (because he didn’t travel there), but

north of the Yangtze river there was nobody who could equal Wang.

Yet there is no Liu He Xin Yi in Da Cheng Quan today. Also, although Wang mentions

weapons (plural), and they supposedly fought with staffs, Wang only taught the

use of the staff in later years, and only to some students.

2. Wu Yihui - of Liu He Ba

Fa fame. Possibly had some influence over Wang. But frankly - can anyone claim

a connection between Liu He Ba Fa and Wang's teachings? I doubt it. Wang did

not mention who won in their fights. However, since there are three people and

the other two amount to 1.5 against Wang, then Wu Yihui was likely the ‘other

1’ to make it

2.5 – meaning Wang considered him to have been superior in

fighting.

3.

Fang Yi Zhuang – Yong Chun White Crane

(Bai He Quan). Out of 10 matches with Wang, each men ‘won’ 5 – making it ‘a

draw’ – hence “only defeated by 2.5 men”. No Southern Crane methods exist in Da

Cheng Quan today.

In

the following videos – good examples of Southern White Crane (Bai He Quan):

Allow

me to explain such stories (of fighting the masters) to those not versed in the

little social intricacies of Chinese culture. The culture that Wang lived in

was and still is today one that strives for social harmony. The best, most

preferable solution to any social issue is to have an outcome where everyone is

pleased, happy and content (better have solidarity than ‘winners’ – everybody

wins is the goal). The Chinese have no trouble lying if it means that this

important goal is achieved, and social harmony is obtained. In writing the

accounts of the masters above, Wang Xiangzhai achieved that goal in a very

typical Chinese way. He mentions the name of a Chinese master as someone who

beat him on a public newspaper to help that teacher gain fame and fortune. At

the same time, he himself gains respect by associating his own name with ‘the

great other teacher’, and claiming to have studied from him. Both sides receive

honourary mentions and publicity. Everyone are content. That is, regardless of

the fact that in truth, we see nothing from the arts practiced by these gentlemen

in the art later taught by Wang.

Even more ironic is that all of the teachers who were hailed by Wang practiced

and taught martial arts which include a very broad curriculum, with countless

techniques and forms (or few extremely long forms). These broad curriculums and

their forms are the same things which Wang later heavily criticized, and

omitted completely from his own art. Much like Bruce Lee, Wang was all too keen

on condemning and ruling out such fixed training methods, even though they were

used by people under whom he claimed to have studied.

After his travels, which lasted about a decade, Wang finally settled in the already booming metropolis of Shanghai. This is likely where he came to know and interact with Liu He Ba Fa master Qu Yihui, whom I had mentioned a few paragraphs ago. At the time in China, prior to the 1930s, good martial arts teachers were far and in-between, and were difficult to locate since there were hardly any phones, newspapers or other means of mass communication and media. Such teachers were highly valued for their transmission of useful survival skills and traditional culture, and were often sought after by rich families to personal tutoring. A martial artist could have earned an incredible salary working for such people, and indeed it was during his time in Shanghai that Wang became a rich man.

He used his money wisely. At one point he went to late Guo Yunshen's village and built a new and fancy tombstone for him, in order to pay his respects, and also cement to view that he was Guo's disciple. The tombstone was unfortunately taken during the Cultural Revolution to be used as construction material. Later a new one was erected during the 1980s.

After his travels, which lasted about a decade, Wang finally settled in the already booming metropolis of Shanghai. This is likely where he came to know and interact with Liu He Ba Fa master Qu Yihui, whom I had mentioned a few paragraphs ago. At the time in China, prior to the 1930s, good martial arts teachers were far and in-between, and were difficult to locate since there were hardly any phones, newspapers or other means of mass communication and media. Such teachers were highly valued for their transmission of useful survival skills and traditional culture, and were often sought after by rich families to personal tutoring. A martial artist could have earned an incredible salary working for such people, and indeed it was during his time in Shanghai that Wang became a rich man.

He used his money wisely. At one point he went to late Guo Yunshen's village and built a new and fancy tombstone for him, in order to pay his respects, and also cement to view that he was Guo's disciple. The tombstone was unfortunately taken during the Cultural Revolution to be used as construction material. Later a new one was erected during the 1980s.

Wang's public declarations about his art, his lineage and the lesser qualities of other arts and teachers did not go unnoticed among the Xing Yi exponents of his day, even if they did not usually care to challenge him to fights directly. Some were not appreciative of the fact that Wang named his art 'Yi

Quan' - a synonym for Xing Yi. He received a 'hint' (likely from Song Shirong) that

he better pick another name (or else…), and that is how the art's real name,

'Da Cheng Quan', was conceived and found common usage. However, few in the West

are aware of these events, which is why the art is still commonly referred to

as 'Yi Quan'.

It is implied by some that Wang’s approach got him in trouble

more than once. This we can see, for instance, in the following passages, taken

from the book ‘Taijiquan and the Search for the Little Old Chinese Man’,

by Adam D. Frank (pages 65, 164-165). These quote two teachers’ account of Wang being kicked out

the Shanghai martial arts scene: “…On

this particular summer evening, we found ourselves engrossed in a discussion of

Yu Pengshi and the practice of yiquan, or “mind-intent boxing.” A disciple of

yiquan’s founder Wang Xiangzhai, Yu Pengshi had been the Lu family’s neighbor.

Yu introduced yiquan to martial artists in the San Francisco Bay Area in the

early 1980s. His wife continued to live and teach there. When we walked through

Teacher Lu’s old neighborhood, he occasionally pointed out the vifilla where Yu

Pengshi had lived. “His gongfu was just OK,” said Lu. “He was a disciple of

Wang Xiangzhai. But Wang Xiangzhai was a braggart. While he was living in

Shanghai in the thirties, he bragged a lot, but he was finally invited to leave

town by some of the other teachers.” The sort of criticism that Lu directed at

Wang Xiangzhai and Yu Pengshi often colored our practice sessions. I usually

refrained from criticizing other arts and teachers; Lu simply spoke his mind…… one

JTA member who grew up next to the disciple of Wang’s who brought yiquan to the

United States simply says, “Wang Xiangzhai chui niu” (literally, “to blow like

a cow”; to brag). This teacher went on to say that Wang was basically hounded

out of Shanghai in the 1930s by some of the other martial arts teachers”.

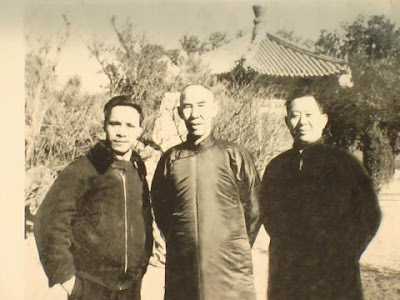

In the picture: Wang Xiangzhai (center) with his

disciple Li Jianyu (left) 李见宇 and their friend Zhou

Bingqian 周秉谦 (right).

One of the few people who did

challenge Wang openly was Kenichi Sawai from Japan, at the time said to

have been a Judo 5th dan and Kendo 6th dan – certainly

skilled in those arts. He was soundly defeated by Wang, and accepted as his

student afterwards. But Wang did not care to teach Sawai himself, and for the

most part Sawai learned the art from his student, Yao Zongxun. A few

years later Kenichi returned to Japan, where he taught that art as his

interpretation, called ‘Tai Ki Ken’. At the time, Wang and Yao’s association

with Sawai, who was a colonel in the Japanese military, gave them social and

physical immunity from harm. But such links were also heavily frowned upon by

most Chinese, and consequently Yao spent some time in prison in the following

years because of such connections. Others in the community even went as far as to refer to Wang's art as 'Traitor Fist' (Hànjiān Quán 汉奸拳) - an extremely negative and insulting derogatory term. This is despite the fact it is not known whether Wang simply accepted Sawai into his school, chose to cooperate with the Japanese or was coerced into such actions against his will. Given the horrendous acts of Japan against China during World War II, it was to be expected that anyone even remotely suspected of having ties with the Japanese to have angered a lot of people. Personally, I think Wang cannot be harshly judged on this account.

After

Wang left Shanghai for either this or that reason, he came to Tianjin, another

metropolis, in close proximity to Beijing the capital. Both these cities hosted

the greatest number of famous masters in China at the time. One of the first

things Wang did in Tianjin was to host a big banquet in honor of Zhang Zhaodong

- a very well known teacher of Xing Yi Quan and Bagua Zhang. This was another

smart financial and political move on Wang's behalf. Zhang was thankful for the

way Wang treated him and for the money Wang bestowed upon him. In return for

Wang's kindness, Zhang did a few things to repay him. Firstly, he openly

declared that he supported Wang's claim of having been Guo Yunshen's disciple

(Guo was technically Zhang's gongfu uncle). Secondly, he took a few pictures

with Wang alongside other teachers to solidify his show of support. Thirdly,

since Wang had no students in his new place of residence, Zhang sent ten of his

students to study under him. Their names were:

Zhao Enqing, Gu Xiaochi, Ma Qichang, Deng Zhisong, Miao Chunyu, Zhang

Zonghui, Zhang Entong, Qiu Zhihe, Zhao Fengyao, Zhao Zuoyao. Only three of them

persisted with Wang in the long run, and received customary names from

him: Zhao Daoxin (Zhao Enqing), Zhang

Daode (Zhang Entong) and Zhao Dahong (Zhao Fengyao). Zhao Daoxin and Qiu Zhihe

(the latter never got a special name from Wang), are often praised as great

examples for masters 'groomed' by Wang, especially since they created they own

martial arts systems (Xin Hui Zhang and Luo Xuan Quan, respectively). However,

it has been pointed out that the creation of 'systems' with 'forms' and a fixed

curriculum is in great contradiction with the teachings of Wang, who wanted to

"emphasize the Yi (Intent and Nei Gong) and do away with the Xing (excess

of shapes, forms and fixed techniques). Like many things relating to Wang, this

subject too is highly controversial. There are those who claim that these two

people actually told their students they did not learn much from Wang (Zhang

Zhaodong was their main teacher), while others consider them to be prime

example of Wang's teachings.

In the following videos – Cui Fushan (the older gentleman), grand-student of Wang Xiangzhai and student of Bu Enfu, demonstrating good gongfu. Please read the video descriptions for some context:

The art changes a

fourth time

Initially Wang went about with his

Xing Yi like any other traditionalist in the art. However, since he liked to

pick up fights he soon found out that despite his talent, and perhaps because

he was not taught the whole thing, it not always worked combatively the way he

hoped for. Being practical he looked at his own personal weaknesses and went

through a long and slow evolution. In the beginning he still taught Xing Yi the

way he learned it, Five Fists and Twelve Animals included. But over the years,

and especially following his experiences with the masters mentioned before, his

own practice and teaching began to change.

Because Wang was already skilled in his art, having trained in it for decades,

he did not need to work on developing his structure. His body already contained

the essence of the style, to the level that he had learned and understood it.

His own practice was then focused on the general movement-vectors and the momentum

of various movements, with the patterns being more casual and less strict. In

Wang's words, emphasizing the Yi at the

expense of the Xing. However, the original art was called Xing Yi for a reason!

That both aspects of the art were equally important.

Late master Wang Xuanjie

performing a Jian Wu of Da Cheng Quan:

Wang does not tell us what he felt

did not work for him, personally. But he was enthusiastic on sharing and

proclaiming “what was wrong” with others who studied, practiced and taught the

art.

The name Xing Yi is comprised of two characters: Xing 形 – Shape, and Yi 意 – Intent or Will. The Xing refers to the external bodily

postures, the many techniques and the forms. The Yi refers to the use of intention and the nei gong. Wang strongly felt that “people became too focused on

the practice of Xing, and neglected to work on their Yi”. Hence the art’s first

name – ‘Yi Quan’ (omitting the Xing). In saying that, he was referring to his

own students as well. He uses this argument to justify the many changes he made

to the art, most notable among them being:

- The practice of Zhan Zhuang became

more important than anything else, and the length of time spent standing had

been extended to the upwards of two hours. This was rarely if ever done before

in Xing Yi. In fact, many Xing Yi teachers advocated reducing the amount of

time spent standing as one’s skill increases.

- In Xing Yi there is the minor

practice of Shi Li 試力 (‘Feeling the Power’) – several movement patterns that

represented general and simplified circles and vectors of power. These were

used to teach one to transition the martial structure developed with Zhan

Zhuang into combative usage, and ease the learning of more intricate mechanics

contained within the 12 Animals. The Shi Li are concept-based rather than

techniques based, meaning they teach how to move and react, and not necessarily

how to apply a specific fighting method. Wang made the Shi Li the focal point

of the art’s moving practice.

- The Five Fists and Twelve Animals

were all reduced into simplified forms of Shi Li themselves. Combinations and

Forms were completely eliminated, and turned into repetitive Shi Li drills that

captured what Wang considered ‘the essence’ of the fist or animal. Later in his

life, even the Shi Li of the animals were done with, as Wang gradually took on

an even more reductionist approach to his training and teaching. Some of Wang’s

students and grand-students had to later re-add their own versions of the 12

animals Shi Li, since the originals were lost.

Like many teachers, Wang made the choice

of teaching what he felt worked for him at his level of understanding and

martial development. However, we should remember that Wang eventually acquired

his excellent skills by practicing traditional Xing Yi Quan most of his life.

For better or worse, most of Wang’s students did not receive the instruction he

himself had gotten, but were taught Wang’s idea how the art will be best

manifested. In doing this, Wang was the exception in the Xing Yi Quan

community. As can be seen in the following lineage chart which I created, the art survived through many lineages for at least 7 generations

since Li Luoneng, usually with far less pronounced modifications than those

Wang made.

When people discuss the

changes Wang had done to his original art, often another key element is missed.

The art was greatly affected by Wang’s eventual omission of the Santi posture,

and shifting the preference to wider combative stances. This is because:

1. San Ti Shi makes Xing Yi

Quan a style that specializes in attacking the opponent’s center of mass and

gravity through a narrow corridor of motion. Shifting to wider stances changed

this quality.

2. As a result, the elbows,

which Xing Yi prefers to keep closer to the center much of the time, were now

often raised and went sideways in practice and application; to accommodate for

the new combative positions.

3. Also changing was the

hallmark of Xing Yi, of using vertical forward-driven circles – the power

vector of Xing Yi’s most essential method, Pi Quan. This trait was Xing Yi’s

legacy from the body method of wielding a spear. With both Santi and the old Pi

Quan gone, these circles were altered as well, becoming less forward-driven,

and used more for manipulating the opponent’s structure and less for hitting.

While it is true that in Da

Cheng Quan, a shorter San Ti is used for Zhan Zhuang and some applications, it

is not the core of the style, but rather is Hun Yuan Zhuang (Cheng Bao Zhuang).

Some of Wang’s students are

credited as having been influenced by Western Boxing (Bu Enfu and Yao Zongxun). It was actually Wang that sent them to learn Boxing and compete in it. This art was considered a novelty in China during the 19th

and 20th centuries, and was often a representation, together with

Wrestling, as a representation of the ‘white man’s strength’. Thus, many

glorification stories were told of Chinese masters defeating Western boxers and

wrestlers. Various Chinese practitioners who came from styles wherein footwork

was slightly lacking were astounded by the mobility of boxers and inspired by

them. Such was the case later with Bruce Lee, who incorporated boxing footwork

and concepts into his Jeet Kune Do. I tend to believe that Wang himself was

also at least moderately influenced by the footwork and rhythm of Western

Boxing, even though he never cared to admit it. He certainly received some other influences from boxing as well, as described here by his student (such as adopting a 'guard position' with the hands in fighting). Wang's daughter, Yufang, confirmed this influence in private conversations with my friend, master Yang Hai, when she was alive (she passed away in 2013).

This influence is seen to the largest extent in the Da Cheng practice method known as

Jian Wu 健舞 (literally:

‘Health Dance’). That practice is essentially what a boxer would call ‘Shadow

Boxing’. The practitioner would move spontaneously between any of the postures

known to him, reflecting either natural flow of energy without the body or

going through an imaginary fight with an opponent. Not only is the method

itself and the rhythm in it reminiscent of Boxing, but also the wider, higher

and more ‘square’ footwork, which often floats around on the balls of one’s

feet. Although the two methods obviously differ in their mechanics and in some of their purposes, the general movement concept is very similar.

This is further easily witnessed in Da Cheng’s preference for diagonal stepping

lines, versus Xing Yi’s liking of linear stepping. Also, in Wang’s changing of

Xing Yi’s forward Plow-Stepping to the diagonal, higher and less rooted

but more mobile Friction-Stepping (Mócā Bù 摩擦步).

In the following video –

one of the best exponents of the art in our time, master Cui Ruibin, performing

a Jian Wu:

Speaking of which - there

are also claims that Wang was influenced by Bagua Zhang, and those who would go

as far as to claim that “there is Bagua in Da Cheng Quan”. There is little to

support that idea, apart from minor similar stepping methods. Wang himself

never mentioned it as far as I know. He even admits to have only met Dong Haichuan and Cheng Tinghua (the founder of Bagua and one his his disciples) when he was a child. Even that claim is problematic, since Wang was born in 1885 and Dong passed away about 3 years prior. Those who claim Wang may have studied Bagua with Cheng Tinghua will be disappointed to find out that he died in 1900, when Wang was only 15 years old.

It should be noted and re-emphasized

that by the time Wang made those profound changes and essentially created his

own style, he was likely over 40 years old, have trained since childhood and

travelled across China, testing his skills. There is no question that he was

enough of an authority over his own material to be making such decisions. The art had also proven itself, at least in terms of fighting, beyond Wang’s own tales, since several of his students and grand-students such as Zhao Daoxin and members of the Yao family were known as fighters. Later on, through Yu Yongnian’s medical research (and fine book), the methods of Wang were also shown to be very beneficial for the treatment of various illnesses.

Wang Binkui 王斌魁 performs Xingyi Quan and Yi quan:

A grand legacy

In 1962, following the death of his

wife, Wang became ill from grief. The illness increased in severity, and in

1963 he was no longer teaching. That year, he suffered from cerebral vascular

rupture (brain hemorrhage) as a side-effect of medicine he used to receive

regularly. Soon after another delivery of the medicine by his grandson, he fell dying into his arms. He was 78 years old.

Even though I believe it is likely

that Wang did not study Xing Yi Quan fully, that does not detract from his

great achievement. On the contrary. From a limited based in his mother art he

continued to evolve, studying under more teachers and expanding his skills and

understanding, until his efforts yielded a fantastic system for fighting and

health cultivation. Wang’s case is similar to the Okinawans, who had originally

studied southern-Chinese martial arts, usually to a limited extent, but were

able to make the most of what they learned and turn it into the immensely

successful traditions of Karate. Like them, Wang proved that one needs not

necessarily learn a full curriculum in order to come up with substance and

quality. These may differ from the original, but can be no less worthy.

Wang’s open teachings of Zhan Zhuang

methods helped spread his art far and wide, and consequently raised the

interest in Xing Yi, Dai Xin Yi and Xin Yi Liu He as well. Previously, though

very beneficial for one’s health and the healing of diseases, Zhang Zhuang were

only known to Daoist monks and a relatively small group of martial artists

across China. From Wang’s teachings they became a folk health practice, and

eventually entered countless parks, communities and even hospitals. Wang’s

grand-student, late master Yu Yongnian, was a doctor, and conducted many

studies of the medical benefits of Zhan Zhuang, of which he published a book.

In recent decades, many other martial arts have begun adopting Zhan Zhuang

methods as well. I have seen practitioners and teachers of styles as varied and

diverse as Chen and Yang styles of Taiji Quan, Bak Mei and Pak Hok Pai

practicing them and claiming them as their own, although historically such

methods were never a part of their curriculum. There are also countless ‘Qi

Gong teachers’ who instruct on Zhan Zhuang (often poorly) as part of what they

teach.

In the picture: Dr. Yu Yongnian,

one of Wang’s notable students, teaching Zhan Zhuang to a group of people.

During Wang’s life but mostly following

Wang’s death, his art also re-influenced many practitioners of Xing Yi Quan,

who used its more Yi-focused approach to training and fighting to augment the

understanding of what they were already practicing. My own Xing Yi lineage

bears such influences.

Several of Wang’s students and

grand-students were known as fighters, and Da Cheng is becoming increasingly

popular among exponent of MMA and San Da as a practice to augment and hone

their fighting skills. Practitioners of Da Cheng, following in Wang’s

footsteps, were also among the first among the Chinese traditionalists to fight

in modern rings and cages during the late 20th and early 21st

centuries.

Today, Da Cheng Quan is more popular

than ever, essentially being taught worldwide. Though I feel that some schools

of it have an almost cultish quality to the way in which they approach their

practice, nonetheless he majority of that community is made of a very positive

crowd. Often, the art succeeds in attracting people who otherwise may have not

considered the martial arts at all, due to its unique character and greater

focus on meditation. Indeed, not everyone are willing to take on a ‘complete

package’ such as offered by a traditional style, like Xing Yi, which demands

much in terms of the extensive curriculum.

Wang was not foolish in his actions, and he was a skilled

martial artists and teacher. The system he created based on very personal and

perhaps 'lacking' interpretation of Xing Yi, with the addition of insight from

much research and experience, yielded a very robust and excellent style, useful

for fighting and health-promotion alike. His approach to martial arts was sound

and practical, and albeit his arrogance he managed to teach well quite a few

distinguished teachers and pass on to them a great deal of knowledge. His version

of Xing Yi reverberated among many schools of the Internally-oriented arts in

China, and inspired and added to many schools of Xing Yi later down the road. Wang

and many of his students and grand-students have also taken the practice of

Zhan Zhuang to a high level not commonly achieved by teachers of Xing Yi, and

had shown through their perseverance what may be achieved with such methods.

Overall, I have a lot of appreciation for his art and teachings. I just wish

that its history and promotion were more accurate, and not so reliant on

newspaper accounts written by the man of himself. Had Wang lived today, I would

have definitely gone studying with him, but perhaps would not have made him a

role model as a human being. Regardless, the name of his art - Da Cheng Quan 大成拳 – ‘Great

Achievement Boxing’ - befits what he had achieved in his lifetime and what came

about through the decades based on what he had taught.______________________________________________

Jonathan Bluestein is best-selling author, martial arts teacher, and head of Blue Jade Martial Arts International. For more articles by shifu Bluestein, his books and classes offered by his organization, visit his website at: www.bluejadesociety.com

You may also subscribe to Shifu Bluestein's youtube channel, which is regularly updated with rare and fascinating martial arts videos:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCR0VUbThdexbXJb9BBSKMbw

All rights of this article are and the pictures within it are reserved to Jonathan Bluestein ©. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission, in writing, from Jonathan Bluestein.

22 comments:

Calling a Wang Xiang Zhai a liar? And claiming a superior understanding of Chinese culture as your 'evidence'? You don't know the facts, so you shouldn't hypothesise in a such a way. Wang's history is probaby over egged, but that's not the issue. Who the fuck are you to cast aspersions - you, the great fraud of IMA.

As for what 'Yi quan is really about', again, this article presents a trivial level of insight. Yi quan is not a historically time limited concept. Yi quan is simply principles and a structure. The structure is designed to help people to explore and unfold their native ability to employ those principles. The structure is the least relevant aspect - the structure evolves over time, changes from person to person, and is adaptive to new insights. The structure is symbiotic with insight and level.

It wouldn't have mattered if Wang had learned from nobody at all. It wouldn't matter if he'd just unfolded yi quan by himself in the mountains. Anyone with a sufficient understanding and dilligence coulad have. You could, if you wanted to. But you don't - you want kudos, even though it's false kudos. Just as, even now, no one can teach you Yi quan. No lineage means anything. All your teacher does is make life easier by providing a more useful structure for you to learn from. Your one of those people who thinks a petty - and in your case poor - structure is 'what matters'.

Having said that, it would be better if almost everyone claiming to practice yi quan, and indeed IMA, and CMA per se in the West, now just fucked off into their fantasy world and didn't come back. You too. If, in some future dark ages, the 'tapes are erased' and the structures of Yi quan are lost, nevertheless, the thing itsef survives and gets re-found, because it's the most basic, and profound, method of all: the principles of wushu, combined with the qualities, dilligence, capabilities and understanding of the practitioner. That would be better - to start again. Just give up. Stop, sit in the dark, and ask yourself, what the fuck do you really know? Nothing. Start again. Stop misleading people - it makes it harder for them to find real wushu.

Everyone is entitled to their opinion. Some write it politely in the form of serious articles and books. Others just throw profanities about. I do not know who you are, but you likely have a good background in the arts. It is a shame you chose to use this venue as a personal attack against me rather than as a useful platform for discussing the points raised in the article.

Given that I have also praised Wang and his art in the article, and have referred readers to some lineages that came down from him, I would not worry about people's ability to "find real wushu". ;-) Cui Ruibin is one excellent modern teacher of the art that I have put a video of above, and generally speaking I think the art is nowadays thriving more than ever and it is easy to find those who will teach it.

"Some write it politely in the form of serious articles and books."

Really? Your writing, from your articles to your book is written in an extremely opinionated and arrogant manner regardless of whether or not that style reflects your true feelings. And they are not 'serious' in the way you appear to imply, they are far more often than not conjecture and personal opinion.

There is some very real irony in calling Wang arrogant and being critical of strong self-promotion through the media of his day given your own endeavors to have people see you as an expert in IMA, and even Chinese arts you don't study, and lets not forget Chinese culture too!

Your article presumes a lot, and is lacking any great depth of understanding not only about the history of the time, but also of Yi Quan, it's influences and reasons for becoming and being what it was.

Again, what a pity that we cannot seem to be able to discuss the article and its contents.

I have never referred to myself as an 'expert', but I thank you for the compliment. Surely, others know much better than I with regard to the arts. As I have written many times in my articles and book, my understandings are merely the result of standing on the shoulders of giants.

You seem to be a knowledgeable person. How about you write better books and articles? I would very much like to learn from your experience. Since you have a lot to share, please do. I will be the first to read your materials, despite what you have written of me on the personal level. In my book I have referred to over 250 sources, in orderly footnotes and a broad bibliography. Not everyone I referenced or quoted necessarily agrees with my opinions, but I respect anyone who can make a sound argument that is helpful for creating a better understanding of the arts. In the event that you indeed possess a superior understanding and can demonstrate that in writing, then I would be happy to make an example of your fine literary achievements and present these to my readers.

I have read Wang's book/translations of articles by him: "Wang Xiangzhai Discusses the essence of combat science" and the "Right Path of Yiquan" translated by Timo Heikkila and Li Jiong. He reminds me of Bruce Lee and criticized kungfu in the same tone. Considering the lack of fighting abilities in most of today's internal martial artists I would say that he was right to criticize it.

Mr. Wang does not seem like an arrogant guy. He stress over and over that he wants to advance Chinese martial arts and improve on it. He comes across as someone who was truly interested in getting at the truth. "I do not dare to say that I have introduced something new, I just follow and spread the tradition of the predecessors..."

"I just wish that my fellow boxes would be willing to advocate, discuss, and investigate combat science ... However, if nobody does this, I wish to start from myself... Even if my body be full of cuts and bruises, my utmost will come true if combat science can be promoted."

And here's the full line to one of your quote: "Those who understand me are wise people, those who condemn me should sit alone in the still of night to listen to their hearts. Anyhow, let them laugh who will, I will not mind. If the true essence of combat science will prosper again, how could personal praise or blame make any difference?"

And he continues "What I worry about is that the famous masters do not inspect and learn from each other and discuss the problems. I fear it is hardly possible to gain the hope of combat science. Anyways, I hope combat science will advance, polish up the goal of the martial way of our society, and wash off the deep rooted bad habits."

He greatly criticize TaiChi and considered most of it to be watered down except for the Yang brothers, whom he considered to be great martial artists. He comes across as some one who is tired of the secrecy and closed-mindedness of the masters of his time. He wants to test, discuss and get at the core of true fighting skill. I wish there was more like him. Kungfu would be better for it.

This article is not impartial.......In origin Xing Yi wasn't a system of Santishi, 5 elements and 12 animals.....so why the hell the Xing part of Xing Yi should be so important? We have to understand that in origin taolu and concatenations didn't exist. We have to mantain an open mind and (with time of course) get rid of all these mental restrictions.....this is what I think. Of course I don't take for granted to being right, I hope is the same for you all.

Oooooooooook, I finished reading all the article and I have to change my previous comment :D

The article is impartial and what I said previously, You already said it in this LOOOOOOONG story.

Anyway, It is a very good story, a well thought article and it is evident that you didn't stop at the superficiality of your style, but that you digged through it. You made me understand even a bit more of what I already knew, so......really good job, man.

Keep up the good work! Bye!

This is just a witch hunt. Wang's writings expressed the tao. Bluestein's writings express the ego.

I thought this was an excellent article. Putting things in an historical contex is very interesting. It is a pity that you have to put up with an over-zealous yi-chaun enthusiast. I have met yi-chaun practitioners and they seem very proud of their art and its effectiveness.

I am also in the process of reading your book and I find it interesting and I think it makes good points but there is a bit of beating around the bush. Hinting at things rather than stating them directly. The internal arts are very straight forward in many ways and can be expressed clearly in English. You are a good writer and I am sure you could do it. I was asked to explain what you ment by dragon. As an example I pulled him directly down towards me and told him resist. He easily resisted. I then pulled spiralling down and he shot pass. Simple. You may disagree with my understanding, and if you say why we may learn something.

Hi

What do you think about neijia family about karate Okinawa? Is it very low opinion ?how can you compare yichuan with Okinawa karate? So if I understand yichuan is low version of xingyi so that if you meet master Yao or cuiruibin our Wang Shang WEN you can teach them and fight them with one hand only?

*what neijia family think about Okinawa karate?

A point that is often not discussed is why a certain martial art was developed. If they were developed for military use then there will be strict routines that can be done in large numbers. Watching Shoalin monastery demonstration is a good example. The techniques will also reflect their use.

Civilian systems can be different. If they are for budding body guards then they have to be able to fight off multiple attackers on their own but the systems they use can be more complex and subtle. Some martial arts are more for show and use in theatre. Jacky Chan is a good modern example here. Then some systems are more cultural heritage. Japanese sword drawing is an instance.

The age of a style also affects the system. The older ones tend to have more bits to them as generations add different ideas and they become more formalised. The founder of Aikido was against formal routines(kata) and yet within a generation there are stick and sword katas.

Does the system try to quickly or slowly develop fighters? Is it for use on the battle field, street or is it a sporting style like modern Judo or MMA. So if you are trying which is best you have to ask best at what. This also leaves out the question of who you comparing. A nine year old Kung fu trained person against a heavy weight boxer. I know which I would bet on.

Thanks bob

One point very important is that in MMA fighting the soul have no reason to fight and no one of the two fighters have real reason to fight.

So one can beat the other in MMA fighting but in real life if one of them for example has rape the sister of the other the reason are different eland the issue also because the one who lost in MMA can have decuplated power by this injustice

When there is a precise reason to fight the soul and the body doesn't act the same like in a ring. Some can lose their force some can be on fire

Hi,

Thanks for the post. I was wondering if you can provide the Chinese characters for Fang Yi Zhuang, the Yongchun Baihe practitioner who fought with Wang Xiang Zai. Do you have any other info on him? I haven't heard his name mentioned in any writings re Yongchun Baihe. I'm curious as I have learnt a little bit of Feeding Crane. Thank you.

"Had Wang lived today, I would have definitely gone studying with him..."

And why would he take you as a student?

I think it is also a good practice to explore why certain people may have painted Wang as being arrogant. Just because it is said, doesn't mean that is the whole truth.

Jonathan, I enjoyed the article, thanks. I think there might be some minor details that could be argued, but your general story is one that I personally tend to agree with, in terms of WXZ's antecedents and skills. I think the topic of Zhan Zhuang and Shi Li sort of missed the mark, in terms of what they really do and their relationship with other arts, but that's another topic for another time.

In regard to WXZ's opinions of Taijiquan, bear in mind that he only met/knew some of the downstream Yang family and their grasp of the art was but a shadow of what Yang Lu Chan had learned in Chen Jiagou.

I'm surprised by how many putative "martial artists" are too shy to sign their own names in support of their online opinions. Most of the real martial artists I know tend to sign their own names. Ah well, each to his own. ;) Thanks again for taking the time to write for everyone.

Mike, thanks for visiting!

Doesnt matter if master Wang has been disciple of GM Guo or not, that is not important thing.

As Yiquan has so much different with its Xing Yi.

The actual event in Shanghai must be clarified enough I think.

Thanks for visiting!

I believe WXZ succeeded in his goal. I think it’s a strange premise to believe that he lacked insight into the “traditional “ martial arts of Tai, Bagua, Xing, etc. I’m sure he had the ability and opportunity to fill in any “gaps” that may have existed in his training. I believe that he did what he set out to do and returned to the essence of his art, not unlike most geniuses do (Bruce Lee).

Additionally, his art produced results. He had renowned fighters, renowned healers, and a deep understanding of the Tao. These arts all started art from simple meditative practices. Their originators all stressed simplicity. Every powerful teaching dissolved into excessive adornment. Can one be a great Christian without reading the Bible or visiting the Vatican? Jesus would say yes. Can one become enlightened without studying the myriad Buddhist “traditions”? The Buddha would say yes. Can one condense an art to its purest form and become realized? I think WXZ proved this. If you read what he wrote and practice deeply what he teaches you can have no doubt.

This is written in the manner of a xing yi practioner who isn’t familiar with yiquan. My teacher is Han xing Qiao and I am closed door. I can tell you factually so many things you are only able to speculate about. Such as Wu wei. My teacher was a student of master Wu first and introduced Wang to Wu. Lhbf is completely woven as typical movements into Han family yiquan. Further my teacher was there when Wang coined yiquan as a formal name, was there as the art was born and the formal representative of Wang in public. He was the one who first moved and called it the health dance, the fist dance. Wang would say, “ show the people yiquan”, and Han would move. Han added tiger and dragon postures from his background. Wang taught my teachers wife ba gua and we practice the core essence of ba gua in Hsyq . I understand you did the best you could but yiquan isn’t a distant dead history, it lives in Hsyq. I am happy to help as Han was a first person witness to most of the history of yiquan up until ww2. Han was Yao’s teacher for 8 years and I can tell you why Yao system is so mistaken and external. And no, Wang didn’t neglect xing. And yes 90% of xing yi is broken just chasing xing, but hey now yiquan is 90% broken just chasing shape once again. I’ve crossed hands with many many practioners and none have what Hsyq has, they have bits and pieces. Wang rediscovered the core of quan fa. Of the origin of xing yi, lhbf, ba gua etc. our primordial source. It’s not a style but it is a method of zhang zhuang. That is the method. And it’s genisis came from the San ti Shi zhuang, But it’s nit held for time. In fact Han states that he couldn’t do it for more than 3-4 minutes. That mistake is Yao’s. Yao made so many mistakes. Argued with Wang. Wang quit speaking with him. Anyway I’m happy to talk if you like. Fb page is history of the Han family. I am an adopted son of the Hans much as Wang adopted Han.

Post a Comment