Ten thousand flowers in spring, the moon in autumn, a cool breeze in summer, snow in winter. If your mind isn't clouded by unnecessary things, this is the best season of your life.

~ Wu-men ~

Thursday, December 29, 2022

Monday, December 26, 2022

Friday, December 23, 2022

Tuesday, December 20, 2022

Saturday, December 17, 2022

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

Self Correction in Taijiquan

Over at Thoughts on Tai Chi, there was an article on muscle memory and self correction. Below is an excerpt. The full post may be read here.

I have written about things as internalising knowledge from practice, how to let it become a property of the body. In this Tai Chi blog, I have tried to explain that you work with your nervous system differently when you do something you really know, something spontaneous and effortless, as after having studied and learned to speak a new language fluently. So you might see this post on “body language” as a companion to this post and read that one first.

The next question, when you understand that there are different ways to use your nervous system and how to access that muscle memory, is much harder and more complicated to answer: How do you learn to spontaneously access that special mode whenever you need it? That place in yourself where everything comes together by itself and you don’t need to think about what to do and how?

To access that mode, or body state, when you practice free push hands with friends, might be easier than if someone challenged you to a fight. How do you do it suddenly and purely by will in everyday life? How do you switch from a normal “daily mode” to a “Tai Chi mode”?

First, before answering that question, I would like to add that one of the biggest assets, as well as one of the biggest problems, in Tai Chi Chuan, is the obsession of details. But the details we deal with are specific details on movement and body mechanics. This obsession and attention to details is really the only way to “get” what Tai Chi body mechanics is and how it should be done, as well as how to internalise this. But at some point, you really need to let go of that learning stage and instead understand how to trust your own body. You can’t really do this until it has become a property of the body.

But here is the problem: We always want to control what we do and have the feeling that we control the situation and what we do. No? You don’t see this as a problem? Well, let me try to explain why this is counter-productive to what we want o achieve.

If you want to be able to always access you greatest skill and knowledge, and really let your Tai Chi work by itself, you really, really, need to learn how to let go of that inherent wish to always control yourself and what you do. Yes, letting your Tai Chi do the work, to be able get into that Tai Chi mode whenever you want to access it, is about standing back, letting go.

Stop making yourself trip is not easy

Yes, for sure, it’s something much easier said than done. Let me illustrate exactly what I mean by offering you a passage of the Taoist classic Zhuangzi:

“When you’re betting for tiles in an archery contest, you shoot with skill.

When you’re betting for fancy belt buckles, you worry about your aim.

And when you’re betting for real gold, you’re a nervous wreck.

Your skill is the same in all three cases – but because one prize means more to you than another,

you let outside considerations weigh on your mind.

He who looks too hard at the outside gets clumsy on the inside.”

― Zhuangzi, The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu

Read a couple of the lines again:

“you let outside considerations weigh on your mind“

“He who looks too hard at the outside gets clumsy on the inside“

Worrying about what you do, about the results, or how you do something, will be detrimental to what you want to achieve. Putting your mind outside of yourself, thinking about what could happen in a certain situation, might be the last thing you want to do.

Recently, I heard a gun expert saying that “you need to let go of technique and rely on your muscle memory”. I believe this is the same regarding many, many things in life. Just look at yourself when you are riding a bicycle. You can go on for hours without caring about how you move your feet and shift your weight.

But as soon as you try to intellectualise and to understand what you are doing when you are riding a bike, you will switch back to the learning stage of using your body, you will move clumsy and might even cause yourself to stumble or fall. What have you done? Well, you have switched from using your nervous system from the “knowing” stage, to the “learning stage”.

So what does this mean for your Tai Chi in practical practice? Yes, when you practice push hands, practice to use an application, or a real self defence or fighting method, or when you practice to punch at something using Tai Chi mechanics, first, you need to learn the details of the body mechanics and learn to use them.

But, if you want to be able to do something spontaneous in practice or in real life, you need to learn how to forget to focus on the details and the mechanics and just do it.

Sunday, December 11, 2022

Competition and Budo

Below is an excerpt from a post that appeared at The Budo Bum. The full post may be read here.

There is a continual discussion in budo about the importance of competition. The argument for competition has two prongs. The first is that you have to learn to perform techniques under stress, and competition is the best way to pressure-test technique. The second is that you have to learn to deal with the unexpected and the only way to do that is in a competitive situation. I agree that you have to be able to perform under stress and that you have to be able to deal with the unexpected. If you’re not learning to do things when you are stressed, and you’re not learning to deal with the unexpected, you’re not learning budo.

I’ve heard a lot of people expound on the stress benefits of competition. The desire to win ramps up the stress, and in judo or full contact karate, the fact that effective technique can hurt, and may even leave you unconscious, ramps it up further. Add the frustration that builds when your adversary prevents your technique from being effective and the stress level can get pretty high. You can certainly learn something about stress in competition.

I know that for most of the time I was competing I found competition stressful. I would get anxious and it would become harder and harder to stay still and not fidget as the match approached. I had to learn to apply breathing and relaxation techniques in order to control the stress so I didn’t become tense and lose my ability to move flexibly and quickly.

Once the match starts the tension can get worse. The more skilful the adversary, the more frustration and stress. It’s a quick check on students getting cocky about the strength of their technique. It is one thing to practice a technique on a partner who isn’t resisting, and another thing to try to throw someone who is trying to throw you. The experience of learning to flow from technique to technique is great. The dynamism and volatility of competition are excellent experiences for many people.

As Rory Miller so eloquently points out in Meditations On Violence, every training methodology includes a fail. That is, there is always a way in which what you are doing fails, and specifically doesn’t mimic the real world. In competition, it’s that fact that there are rules limiting what you can do, and what your partner can do to you. The possibilities are artificially limited so people can compete with a reasonable expectation that they will be safe and healthy at the end of the competition. Just think of all the techniques that are excluded. Or the protective gear that is worn. Then there is the referee who is there to award points, but also to make sure no one does anything harmful.

This is a safe environment to train in. And the stress level never gets too high because we know it is safe going in. As much as it is a pressure-testing experience, the fact that we don’t have to worry about someone taking a shot at our throat or eyes, or attempting to destroy our knees or elbows means that we’re not experiencing anywhere near the pressure of dealing with someone who genuinely wants to harm us.

There are different kinds and levels of stress. I’ve never seen evidence that competition can rise to anywhere near the level of stress and fear and adrenaline dump that a confrontation outside the tournament area and outside the tournament rules produces. When someone swings a knife at you, the feeling in your gut is quite different from the one when someone is trying to pound you with the ground or choke you unconscious in a tournament. The fear and the adrenaline hit you much harder. That doesn’t make competition useless; we just shouldn’t think it can do something it’s not specifically designed for.

Thursday, December 08, 2022

Monday, December 05, 2022

Friday, December 02, 2022

Lessons from Steven Seagal's Aikido

Below is a video from Aikidoflow on some lessons learned in Aikido, after training with Steven Seagal.

Wednesday, November 30, 2022

The Politics of Olympic Karate

Over at Kung Fu Tea was an article about the politics behind Karate becoming an Olympic sport. Below is an excerpt. The full post may be read here.

Introduction

We are very pleased to host the following essay on Karate’s appearance in the Tokyo Olympics by Prof. Stephen Chan. This is an important topic, particularly to readers who follow the debates surrounding the inclusion and exclusion of certain sports from the games. Yet his discussion transcends the more common narrative of nationally bounded scorekeeping and instead asks what other sorts of work Karate’s Olympic moment accomplished.

Prof. Chan is a founding figure within the Martial Arts Studies community who delivered the first keynote address kicking-off what has since became our annual series of Martial Arts Studies conferences. He is an accomplished practitioner of karate, martial arts instructor and a distinguished political scientist whose writing I have always enjoyed. It is truly a pleasure to welcome him back to Kung Fu Tea.

The Politics of an Olympic Medal

by Stephen Chan

Among karate practitioners internationally the advent of their sport in the Tokyo Olympics, after years of campaigning, was eagerly awaited – but curiously not so much in Japan itself; and the reason for this was its image of violence, not necessarily in the sport itself with its elaborate (though not always successful) safety rules, but in its perceived sociological niche as a working class pursuit. Ju jutsu was, in the same stereotyping, a pursuit of Yakuza and other gangsters. Ju jutsu’s refinement as judo, alongside sumo, kendo, aikido, kyudo (archery) and above all iaido were the sports of gentlemen, or had been accepted at court, and were, moreover, (with the exception of judo) more authentically and historically Japanese. However, judo had been refined enough to pass muster, but karate was without noble pedigree and never quite lost its tag of origin in Okinawa, the most ‘backward’ of the Japanese islands.

These are generalisations to be sure but, despite all the increasing overlays of sophistication and efforts to render karate a martial art equal to the others, it probably took the modern phenomenon of manga with its heroes and villains deploying karate techniques to bring it towards public acceptance.

In Olympic terms, the success of South Korea’s tae kwon do with its development of clearly derivative techniques (despite the Korean claim to its own historical authenticity) was a goad to having, finally, its karate ancestor placed alongside it as an Olympic sport. The leverage of the previous Japanese prime minister, Yoshihide Suga, long a powerful politician and himself a karate third degree black belt – a person who rose from exactly a poor farming and working class background – helped greatly with the campaign for karate’s inclusion. Suga’s well-advertised physical fitness routine which includes 200 situps every day meant it was difficult for more sedentary politicians to gainsay him.

But karate’s inclusion in the Tokyo Olympics meant that Japan had two martial arts represented – karate and judo. South Korea had one, tae kwon do. China has none of its martial arts in the Olympics. Karate’s entry was always going to be tenuous in the terms of the numbers game as to who gets how many of which sports.

If Japan was in this sense in a weak position to insist on karate’s inclusion in the forthcoming Paris Olympics – it already had judo – then other countries were not going to act as karate’s champion. Karate is strong in France, but the international governing body, the World Karate Federation (WKF), does not command total support from the karate community in the USA; and its affiliate in the UK, the English Karate Federation (EKF) has no throw-weight in UK sporting or Olympic politics. Without the two Anglophonic giants of world sports insisting on karate continuing in the Olympics its dropping from the Paris agenda was accomplished with barely a murmur of protest from sporting establishments with quite enough already on their agendas.

Moreover, it has to be said that the Tokyo Olympics featured bouts of sometimes dubious quality and certainly enigmatic judging. As a spectator-friendly event, karate appealed to afficionados but not very many others. There was no wave afterwards of members of the public seeking to learn karate.

As for the WKF itself, it is a strange survivor of internecine struggles that have bedevilled karate since its inception as a sport with international participants. Particularly in the USA there were ‘world championships’ that featured in the 1960s and into the 70s almost entirely American entrants – some of whom went on to become movie stars, such as Chuck Norris, and who certainly featured on the covers of the karate magazines of that era – so that the glamour, and also lack of any international regulatory environment, made karate seem almost splendidly anarchic as the Bruce Lee era dawned. With the dawning precisely of that era, regulatory regularity at least became desirable if only to avoid injuries and their almost random causation.

Sunday, November 27, 2022

Mental Toughness

Below is an excerpt from an article about running and developing mental toughness. I used to be a distance runner and I consider the practice to be "Budo with a small 'b'." It's not strictly Budo, but is a practice that serves to enhance your budo training.

The full post may be read here.

A few years ago, scientist Ashley Samson embarked on a project aimed at accessing the darkest recesses of the runner’s mind. What goes on in the minds of people who voluntarily expose themselves on a regular basis to the rigors and stress of long-distance running? Samson is attached to California State University and also runs a private clinic for athletes who wish to avail themselves of her expertise as a sports psychologist. Samson was an athlete herself in her younger years and she still runs ultramarathons, so she knows all about the mental trials of running.

Up until recently the only way to get inside the heads of long-distance runners was to ask them to fill out a questionnaire after a race. Not exactly what you would call a reliable method, as it is always uncertain how well people remember specific information after the event. Samson and her colleagues decided to try something different. They fitted 10 runners with microphones and asked them to articulate their thoughts freely and without any self-observation while out on a long run. The scientists then listened to all 18 hours of the recorded material, searching for patterns. The thinking-aloud protocol allowed only immediate thoughts to be recorded; thinking aloud actually stops the mind from wandering. Nevertheless, the scientists must have had great fun listening to the recordings. “Holy shit, I’m so wet [from all the sweat],” reported Bill. “Breathe, try to relax. Relax your neck and shoulders,” said Jenny. Bill found the going very tough: “Hill, you’re a bitch . . . it’s long and hot. God damn it . . . mother eff-er.” Fred paid more attention to his surroundings: “Is that a rabbit at the end of the road? Oh yeah, how cute.”

Samson categorized the thoughts into a series of themes. Three themes in particular emerged: pace and distance; pain and discomfort; and environment. All of the participants in Samson’s experiment experienced some level of discomfort, especially at the beginning of their run. For example, they suffered from stiff legs and minor hip pain that became less severe the longer they ran. To cope with the pain and discomfort, the runners used a variety of mental strategies, including breathing techniques and urging themselves on.

There is more to running than just training your muscles and improving your stamina. It is also a mental sport, and maybe even more so than previously believed. Most runners appreciate the importance of mental strength. Those who decide to join their colleagues for a 10K run without any prior training are often able to show just how far you can get on motivation and perseverance alone. They run on “mental energy” and spur each other on. Keep going! Never mind the pain! As for ultramarathon runners, instead of ignoring pain they embrace it as part of the whole experience of long-distance running. “Pain is inevitable” is their mantra; it is an essential ingredient of the running experience. So what are the psychological qualities that make you a good runner? To what extent do they influence performance? And most importantly: Can you train mental toughness?

The Psychology of Performance

Anyone who wants to know more about the psychological side of sports would be well advised to talk to Vana Hutter. She is an expert on the mental health of top-class athletes, and she sums up all of the research on the matter as follows: Top-class athletes are armed with high levels of self-confidence, dedication, and focus, as well as the ability to concentrate and handle pressure. Their academic performance and social skills are also often better than that of nonathletic types. According to Hutter, athletes need self-regulation in order to perform. Everyone can learn, to some extent at least, to control their emotions, thoughts, and actions. And it is this aspect — learning to self-regulate — that is of particular interest to runners.

Funnily enough, Hutter began her scientific career at the “hardcore” end of exercise physiology: physical measurements of athletes’ bodies. “As time went on, however, I realized that athletic performance is determined by a combination of body and mind,” she tells me over coffee in Amsterdam. “I discovered that it is far more difficult to predict athletic performance than some physiologists would have you believe. There are so many factors that we just can’t account for.” For example, how do you explain the fact that the times athletes run are so different despite their being physically very similar?

If you were to subject the top 10 marathon runners to a physiological examination, they would probably all have a high VO₂max and excellent running economy. Some top athletes have something extra as well, however. “Measured over a longer period, the trainability of athletes is more or less the same. What really matters during competition is the extent to which their physiological systems are primed and ready to go, and how well those systems cooperate with each other,” explains Hutter. “Whether an athlete can avail of their maximum physical potential at the crucial moment is partly a mental matter.”

She provides an example. “If your muscles are a little bit more tense because you are nervous, this will have an effect on your movement efficiency. You will need more energy to achieve the same kind of forward motion. This is the biomechanical explanation of the role of psychology in performance. On the other side of the spectrum, nervous anxiety can result in negative thoughts and fear of failure.” In other words, to go far as an athlete you need not only the right kind of physique but also to be mentally strong, primarily because of the influence the psyche has on how the physical body performs. Mental strength may in fact be the thing that separates the winners from the rest of us. Today, no one denies the role played by psychology in athletic performance. However, the extent to which coaches address mental toughness when training their athletes is a different matter, according to Hutter. Most of them do integrate it in their training, but opinions vary greatly on just how trainable mental toughness actually is.

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Steven Seagal's Aikido

Say what you want about Steven Seagal. I like his aikido. Even though he is not the young man he once was, he still moves as smooth as glass. Below is a 15 minute documentary on his martial art.

Monday, November 21, 2022

Was Bruce Lee Right About Fixed Patterns?

Over at JDK HQ|Taekwondo Perth was an article that examined Bruce Lee's ideas on fixed pattern practice and how those ideas impact the practice of a traditional martial art. An excerpt is below. The full post may be read here.

It's ironic. The Founder of JKD, that's Jeet Kune Do, and attributed as the Father of MMA, Bruce Lee was brought up schooled in Wing Chun. A talented athlete with a keen intellect, he assessed the tactical strengths of his traditional martial skills (based on those fixed patterns), and then reached for and assimilated new skills to round off his fighting base.

Friday, November 18, 2022

Turning the Waist in Taijiquan

Turning, not twisting the waist is a foundational principal of taijiquan movement. Below is an excerpt from a post that appeared at Thoughts on Tai Chi on that topic. The full post may be read here.

What does “waist” mean in Tai Chi Chuan? Isn’t the waist just the waist? Is it necessary to complicate it and analyse the meaning of this common word? Well, first, Chinese is obviously another language than English. And we know that words don’t always have the exact same meaning in different languages.

Still, this post might seem provocative, as everyone translate the Chinese character “yao” into “waist”, including the most famous “Masters” today who travel around the World to personally sign their commercial books at two-day seminars for many hundreds of participants, eagerly waiting to learn about the deep secrets of Tai Chi that are reserved for only a chosen few. I guess that having a master, or even Grandmaster(!), signing their book make many students feel as they have achieved “more” through their training.

But as I myself am neither famous or travel around signing books, I couldn’t care less about the commercial aspects of being politically Tai Chi correct. So let’s start from the beginning by explaining the Chinese character for “waist“.

In the Tai Chi Classics, this character is “yao” or 腰. This character, that belongs to 3000 most common characters (Ranked no. 1228 to be precise), or Yao, is indeed a common Chinese word for what we mean by waist, or the area around the back and belly, between the ribs and the hips. This is that makes the upper body rotate horizontally while the lower part of the body remains mor or less stable. In Western tradition the waist is what separate the upper and lower body. And sure, we can use “yao” in this sense as well. Yao can be used for “waistline” and the word for belt in Chinese is yaodai, 腰带.

So where, and in what context, do we use the character yao in Tai Chi? Well, It’s right there in the Tai Chi Classics, in the probably most common and well known Tai Chi saying:

其根在脚,

发于腿,

主宰于腰,

形于手指

Rooted in the feet,

fa/issue through the legs,

controlled by the yao,

expressed through the fingers.

What many masters on many books have explained, and what I would believe that most Tai Chi practitioners should agree on, is that everything must move together as a whole, as one single movement. Foot, legs, yao, arm and hand. Well, “shou” 手 or “hand” can be used for the whole arm as well. So you could interpret this character, here in this context, as the whole arm, right out to the fingers. When one part moves, the rest of the parts move at the same time. Everything should have a direct connection through movement.

Okay then, let’s go back to the yao. What you need to know is that Chinese people don’t necessarily associate character yao in the same way Western people do with waist. In Chinese, Yao can mean “waist”. But foremost, this character is associated with the lower back. One common translation you can see in dictionaries is in fact: the lower back.

Tuesday, November 15, 2022

Examing the Slow Practice of Taijiquan

Ever wonder why Taijiquan is generally practiced slowly? Below is an excerpt from a post that appeared at Slanted Flying, which examines that topic. The full post may be read here.

A common joke about t’ai chi is about a practitioner who is confronted by a bully to fight. The practitioner agrees to go outside and fight, but tells the bully, “it will have to be in slow motion!” The popular misconception about t’ai chi is that the practice is just a slow motion dance, and many people are surprised that it is also a highly skilled martial art. But what about this slow motion aspect?

Different speeds produce different effects for learning. At fast speeds one can appreciate the momentum of swinging and turning as well as experience the force of strikes, but it is too fast to attend to details and subtleties. Medium speed is perhaps a balance between learning momentum and balance, but still does not provide the detailed attention necessary for exploring nuances of movement.

When moving fast through forms, one set of muscles becomes active to initiate the movement and another stops the movement. Between initiation and stopping there are many other processes occurring, but we move so rapidly we seldom notice them. Slow movement enables us to pay closer attention to relaxing muscles that are not needed for the movement, aligning and sinking the body, relaxing abdominal breathing (we tend to hold it or breathe in the upper chest when concentrating), and linking and coordinating all parts of the body.

Learning t’ai chi is a complex motor process. Consider the principles of posture from the classics: Keep the head upright, hollow the chest, relax the waist, differentiate substantial and insubstantial, sink the shoulders and drop the elbows, coordinate upper and lower parts of the body, and so on. Each of these requires close attention and practice, let alone how they are all finally integrated into the flowing movements of t’ai chi. Slow and repetitive practice allows attending to each one and gradually integrating them into a fluid form.

A common joke about t’ai chi is about a practitioner who is confronted by a bully to fight. The practitioner agrees to go outside and fight, but tells the bully, “it will have to be in slow motion!” The popular misconception about t’ai chi is that the practice is just a slow motion dance, and many people are surprised that it is also a highly skilled martial art. But what about this slow motion aspect?

Different speeds produce different effects for learning. At fast speeds one can appreciate the momentum of swinging and turning as well as experience the force of strikes, but it is too fast to attend to details and subtleties. Medium speed is perhaps a balance between learning momentum and balance, but still does not provide the detailed attention necessary for exploring nuances of movement.

When moving fast through forms, one set of muscles becomes active to initiate the movement and another stops the movement. Between initiation and stopping there are many other processes occurring, but we move so rapidly we seldom notice them. Slow movement enables us to pay closer attention to relaxing muscles that are not needed for the movement, aligning and sinking the body, relaxing abdominal breathing (we tend to hold it or breathe in the upper chest when concentrating), and linking and coordinating all parts of the body.

Learning t’ai chi is a complex motor process. Consider the principles of posture from the classics: Keep the head upright, hollow the chest, relax the waist, differentiate substantial and insubstantial, sink the shoulders and drop the elbows, coordinate upper and lower parts of the body, and so on. Each of these requires close attention and practice, let alone how they are all finally integrated into the flowing movements of t’ai chi. Slow and repetitive practice allows attending to each one and gradually integrating them into a fluid form.

Saturday, November 12, 2022

Wednesday, November 09, 2022

What it is to be a Samurai

Below is an excerpt from a post that appeared at The Budo Bum. The full post may be read here.

So you want to be a samurai, eh? When I ask people who revere the samurai “What is it about the samurai that you find so great?” The most common answer is that they are impressed by the bushido code. There is a lot of good stuff found in what is termed the bushido code. Most of it predates the bushi by 1500 years or more, and the rest was added in the early 20th century when the term “bushido” was first widely used. Most of the stuff about sacrificing oneself for one’s lord other such more extreme was only added in the early 20th century.

The parts of “bushido” that weren’t added by fascist military promoters in the 20th century are quite good. It's just that they are basically the 5 virtues of Confucius. I have a piece of calligraphy in my living room done by my budo teacher, Kiyama Hiroshi Shihan, that lists them in this order:

智 仁 義 礼 信

In Japanese they are read:

Chi 智 or “wisdom”.

Jin 仁 or ”benevolence”

Gi 義 or “righteousness”

Rei 禮 or “ritual propriety”

Shin 信 or “Trust”

These all seem like really good virtues, especially if you understand a little about Confucian thought. I can’t think of anyone who would argue that chi, or wisdom, is a bad thing. Developing wisdom requires having some understanding of the world, so study and learning is encouraged as a means of acquiring wisdom. This includes active, lifelong studying for self-improvement. Once you have some wisdom and understanding, you have to act on it. Wisdom without action isn’t really wisdom.

Sunday, November 06, 2022

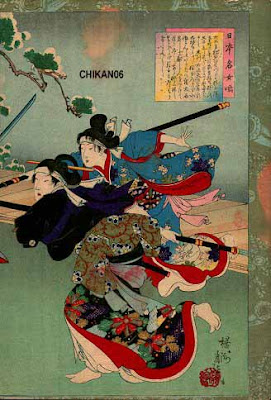

Chinese Opera

This is an aria of a Chinese opera styling dated 500 years ago. The soprano sings and performs martial art play in "Kun" style. The story is about an heroine fable killing an evil monster for the good of the people.

Thursday, November 03, 2022

Monday, October 31, 2022

Friday, October 28, 2022

Seeking the True Way

Over at Kenshi 24/7 there was an excellent post on they study of Budo through Kendo. I think the post would benefit anyone who studies martial arts. Below is an excerpt. The full post may be read here.

Those who seek to study kendo must never forget to follow The Way ("michi"). People follow a path to a destination, there is no need to rush down it; instead follow it correctly. In other words, following a path accurately is something that naturally protects the person who walks down it.

If you truly seek this way, you must first (aim to) cultivate/discipline the self, and with this spirit face your opponent. This is the essential meaning of kendo. All humans have (or have the potential to have) a beautiful spirit; through self cultivation you can work to share this with others.

If you forget this spirit and merely find joy in striking and defeating opponents, well that isn't real kendo.

People who do kendo shugyo should seek the true way their entire lives and become a good *person.

Tuesday, October 25, 2022

French Cane Fighting

Canne de Combat, French cane fighting, is a French combat sport. Below is short documentary on the sport.

Saturday, October 22, 2022

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

Kagoshima's Samurai Heritage

Below is an excerpt from an article that appeared at the Japan Travel website. The full post may be read here.

Try Jigen-ryu, the martial art practiced by Satsuma’s samurai

The samurai of the Satsuma Domain were known to be some of the strongest in Japan, and they trained every day, practicing a martial art called Jigen-ryu. Their strength is credited to the techniques of Jigen-ryu and the mindset it promotes.

Jigen-ryu instructs its followers that “swords should not be drawn,” and strongly cautions against unnecessary killing. However, it also emphasizes that when danger strikes, a warrior should be prepared to cut an enemy down in a state of mind free of all thoughts and desires. Jigen-ryu places importance on making the first move and putting everything into that first strike to bring about victory in a quick, sharp slash. The martial art was established between the late 16th and early 17th century and has a history of over 400 years. The teachings of Jigen-ryu were considered secret, and the Satsuma samurai had a duty to prevent the techniques from becoming known outside of the domain.

At the Jigen-ryu Swordsmanship Museum, you can bring both your body and mind closer to that of the samurai. Try out tategi-uchi, a basic and essential form of training in which the swordsman hits an upright wooden pole with a wooden stick the same length and weight as a katana. This helps a warrior to swing a katana confidently and with strength, without unnecessary movements of the body. The samurai of Satsuma were instructed to strike the tategi 3,000 times in the morning and 8,000 times in the evening. Visitors to the Jigen-ryu Swordsmanship Museum can experience tategi-uchi with an advance reservation. Loose fitting clothing and a towel is recommended.

Sunday, October 16, 2022

Birthday 2022

Today is my birthday. Won't you help me celebrate?

I have successfully completed another trip around the sun.

I have just completed 1 year at my present job. Of course, something had to happen along the way.

As I was nearing the one year anniversary at work, I received an email from HR (I have come to hate emails from HR). Between my age and my years of service (1), I was eligible for an early retirement incentive program.

Great. The plan has been to retire in another 18 months (when I hit full retirement age), but with crazy inflation and a recession, it looks like I'll probably want to keep working until I'm 70, if I can. Now I was looking at taking the incentive and rolling the dice that I could find another job, not taking the incentive and rolling the dice that I don't get laid off (as there is obviously a reduction in force program going); and hoping I can get back to work in the event I do, or nothing happens.

Just in case, I made contact with a former customer who is the CEO of a competitor now. I have a lifeboat with him. I'd have to agree to work until I'm 70 and to justify my salary, I'd have to wear many hats; but it's a lifeboat.

My wife and I sweated this out over a long weekend, going over all the scenarios. When I spoke to my boss, he tells me that I wasn't supposed to get that email. Our part of the company was newly acquired and the corporation's intent was to leave the newly acquired companies alone for them to get their legs under them.

It was a relief that I wasn't getting pushed out. But we are in a recession and there is a workforce reduction taking place. I expect anything to happen.

One of my daughters was married this summer. It was a beautiful wedding in northern Michigan. She had one of the best weddings I had ever attended. They did a great job putting that together.

Unfortunately, my other daughter has just been laid off. She's busy looking for a new job, but is also enjoying her time off.

I am practicing the best taijiquan of my life right now. I've had many breakthroughs over the past year. As far as my practice goes, I am in a good place.

I've decided to keep track of how many book I've read this year. I'm on track to read 50 books.

Everyone's health is good. Although we all expect some rocky times ahead, due to the economy, we're all in a good place.