Decades ago, when I was a young software engineer, I had a job where I sat next to a PhD from Taiwan. He took an interest in me because I was practicing taijiquan and had an interest in Asian things.

Every day he would write out a character for me and explain it to me. The one that really stuck with me was “change.”

If you’re stuck, change. If something isn’t working, change. If your mind isn’t right about something, change it.

As martial artists, change is one of the fingerposts of what we do.

Below is an excerpt from a post from author Steven Pressfield's blog on the topic of change and why it is so difficult. The full post may be read here.

In his wonderful book The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves, psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz tells the story of Marissa Panigrosso, who worked on the 98th floor of the South Tower of the World Trade Center. She recalled that when the first plane hit the North Tower on September 11, 2001, a wave of hot air came through her glass windows as intense as opening a pizza oven.

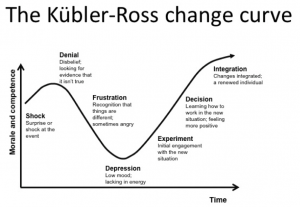

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s Seminal Change Curve is Story-Driven

She did not hesitate. She didn’t even pick up her purse, make a phone call or turn off her computer. She walked quickly to the nearest emergency exit, pushed through the door and began the ninety-eight-stairway decent to the ground. What she found curious is that far more people chose to stay right where they were. They made outside calls and even an entire group of colleagues went into their previously scheduled meeting.

Why would they choose to stay in such a vulnerable place in such an extreme circumstance?

Because they were human beings and human beings find change to be extremely difficult, practically impossible. To leave without being instructed to leave was a risk. What were the chances of another plane hitting their tower, really? And if they did leave, wouldn’t their colleagues think that they were over-reacting, running in fear? They should stay calm and wait for help, maintain an even keel. And that’s what they did. I probably would have too.

Grosz suggests that the reason every single person in the South Tower didn’t immediately leave the building is that they did not have a familiar story in their minds to guide them.

We are vehemently faithful to our own view of the world, our story. We want to know what new story we’re stepping into before we exit the old one. We don’t want an exit if we don’t know exactly where it is going to take us, even—or perhaps especially—in an emergency. This is so, I hasten to add, whether we are patients or psychoanalysts.

Even among those people who chose to leave, there were some who went back to the floor to retrieve personal belongings they couldn’t bear to part with. One woman was walking down alongside Marissa Panigrosso when she stopped herself and went back upstairs to get the baby pictures of her children left on her desk. To lose them was too much for her to accept. The decision was fatal.

When human beings are faced with chaotic circumstances, our impulse is to stay safe by doing what we’ve always done before. To change our course of action seems far riskier than to keep on keeping on. To change anything about our lives, even our choice of toothpaste, causes great anxiety.

How we are convinced finally to change is by hearing stories of other people who risked and triumphed. Not some easy triumph, either. But a hard fought one that takes every ounce of the protagonist’s inner fortitude. Because that’s what it takes in real life to leave a dysfunctional relationship, move to a new city, or quit your job. It just does.

I think it is because change requires loss. And the prospect of loss is far more powerful than potential gain. It’s difficult to imagine what a change will do to us. This is why we need stories so desperately.

No comments:

Post a Comment