At the Isshindo blog, there was a a post about Isshin no jotai, "the state of one heart, one mind." An excerpt is below. The full post may be read here.

Isshin no jōtai [一心の状態]

The Japanese concept of Isshin (一心) can be translated as “one heart” or “one mind.” It signifies a state of complete concentration, focus, and unity of intention, where the mind and heart are aligned toward a single goal or purpose. In martial arts and other disciplines, Isshin embodies the idea of wholehearted commitment to an action or task, with no distractions or divided attention.

Core Meanings of Isshin:

1. Undivided Focus: Isshin represents a state of undivided focus or single-mindedness. In martial arts, this can mean that the practitioner must be fully immersed in the moment, acting with full attention and intention without allowing external thoughts to interfere. Whether performing a kata, sparring, or responding to a threat, the martial artist must unify mind and body in the present action.

2. Heart and Mind as One: The term “心” (shin or “heart-mind”) refers to both cognitive and emotional aspects in Japanese thought. Therefore, Isshin suggests not just mental focus but also emotional dedication, merging the rational mind with feelings like passion, determination, or even serenity. In practice, this can mean acting with full sincerity, whether in physical movements or personal interactions.

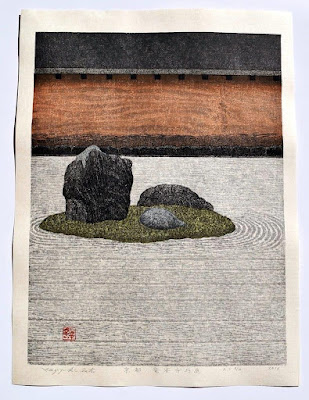

3. Spiritual Undertone: In a broader, spiritual context, Isshin can reflect the principle of purity of purpose—having a clear, unobstructed path between one’s intentions and actions. This idea aligns with various Japanese spiritual and philosophical traditions, such as Zen Buddhism, where one cultivates a state of awareness that transcends the ego or distractions, acting with clarity and purpose in every moment.

4. Isshin in Martial Arts:

• Karate: In karate, Isshin is particularly important because it enables practitioners to act decisively and with full commitment in every strike, block, or movement. Hesitation, second-guessing, or a wandering mind could create openings for an opponent, making full focus essential. This concept also encourages karateka to unify their techniques, spirit, and intentions into one, bringing everything into a singular, cohesive action.

• Other Budo Disciplines: Similarly, Isshin applies to other Japanese martial arts like kendo, aikido, or judo. It is often associated with quick, decisive actions and perfect timing (e.g., when an opening presents itself, the practitioner must act immediately with full presence).

5. Application Beyond Martial Arts:

In Japanese culture, the concept of Isshin extends beyond martial arts. It can apply to various crafts, professions, and even daily life, reflecting the importance of doing things wholeheartedly. Whether an artisan is working on a piece of pottery, a chef is preparing a meal, or someone is simply conversing with another person, Isshin signifies complete immersion and sincerity in the act.