Although I am mostly interested in what might be termed "traditional" martial arts, there is something fascinating about a martial sport that tries to get as close as possible to "the real thing."

What follows is an excerpt from an article at the New York Times website. If you click on the link you'll be directed to the full article, which has loads of pictures, links, etc.

June 22, 2006

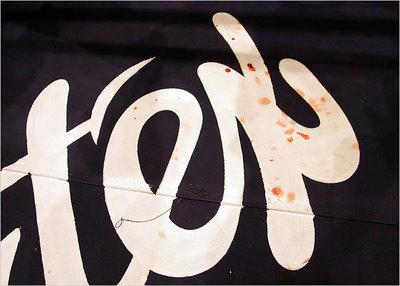

No Holds (or Kicks, or Punches) Barred

By LEE JENKINS

On the morning of June 4, as the graduating class at Chelmsford High School in Massachusetts flocked to a football stadium for commencement, Chris Fox took a Greyhound bus to the Howard Johnson Hotel in Atlantic City.

The other seniors at Chelmsford High were about to receive their diplomas. Fox, 17, was about to get started on the next phase of his education: how to punch, kick and karate chop another man into bloody submission.

"I think I'm the only one missing my high school graduation to be here," Fox said. "But I knew it would be worth it."

He sat cross-legged in a ballroom, alongside about 140 other young men in workout clothes. Some had flown across the country. Others had driven all night. They were there not necessarily because they planned to be professional fighters, but because they wanted to learn under the best fighter in the world.

His name is Fedor Emelianenko, and in the sport of mixed martial arts, he is Mike Tyson, circa 1988. He draws more than 60,000 fans for his fights, makes more than $1 million a bout and rarely needs more than a couple of minutes to complete his work. He enters the ring looking out of shape and half-asleep. Then he begins stomping the head of the next challenger.

But as Emelianenko strode into the Howard Johnson, flanked by a United Nations interpreter and five ring girls clad in red satin, no one at the front desk recognized him. Mixed martial arts is still in the formative stages, a sport chronicled mainly on the Internet and fueled at the grass-roots level. Only when Emelianenko reached the ballroom, where he was to conduct a fighting seminar in his native Russian, did young men whisper and squeal.

"I never thought I could achieve so much this way," Emelianenko said through an interpreter.

"But it was always my dream. It was my golden dream."

The dream, to parlay karate or wrestling or street-fighting skills into fame and riches, has spawned thousands of Americans in training. Teenagers practice mixed martial arts in local karate gyms for the same reason they play baseball for traveling teams. They hope someday to be good enough to make the major leagues.

Mixed martial arts includes two major leagues: the Ultimate Fighting Championship, which is famous in the United States for its pay-per-view showdowns, its octagonal ring and its highly rated reality television show; and Pride Fighting Championships, which is most popular in Asia, regularly fills the Tokyo Dome in Japan and has enough money to keep Emelianenko on its roster.

But there are dozens of smaller leagues, like Mixed Fighting Championship, International Fight League, Gladiator Challenge, TKO, K-1, M-1, King of the Cage and Cage Rage, that help less-acclaimed extreme fighters stay in the ring. Some make as little as $500 a bout, pay their own expenses and share hotel rooms with whichever friends have agreed to train and manage them.

"I guess I'm a dreamer," said Joey Brown, a 39-year-old fighter from Lodi, N.J., who goes by the nickname Knockdown. "It takes a dreamer to do what we're doing."

Brown has a full-time job, a 1-5 record and an assistant manager he pays by helping to baby-sit her mentally disabled daughter. He works days for an auto parts company in North Jersey and trains nights at a gym in Manhattan. From the moment Brown saw the first Ultimate Fighting Championship — "Nov. 12, 1993," he recited proudly — he found a sport that spoke to him.

Mixed martial arts is for anyone who has wrestled, boxed or kick-boxed, anyone who has done jujitsu or tae kwon do or muay Thai. The sport was invented to give those fighters a professional outlet and to determine which discipline was best. Would a boxer beat a wrestler? Would a jujitsu master take out a tae kwon do specialist?

The night before Emelianenko's seminar, 22 fighters gathered at the Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, in part to help answer those eternal questions. They were all on the card for Mixed Fighting Championship 7, with the main event pitting a former high school wrestler from Philadelphia against a former marine from Canton, Ill.

The wrestler, Eddie Alvarez, had passed up a college scholarship to be a mixed martial artist. The marine, Derrick Noble, had a degree in kinesiology, was working on a master's in athletic administration and had interned for the Chicago Bulls. "I don't really think I can do this for a living," said Noble, 27. "But that's still the goal."

No comments:

Post a Comment