A documentary on Shorin Ji Kempo.

Monday, November 30, 2015

Friday, November 27, 2015

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

The Aikido of Hiroshi Isoyama

Hiroshi Isoyama has been training in Aikido since he was twelve. He's nearly 80 now.

He is known for his aggressive style and was a great influence on Steven Seagal, which you can easily see in the video below.

As with most Aikido Demonstrations, I wish the Uke had been a little less compliant, but the breakfalls are breathtaking.

Enjoy.

He is known for his aggressive style and was a great influence on Steven Seagal, which you can easily see in the video below.

As with most Aikido Demonstrations, I wish the Uke had been a little less compliant, but the breakfalls are breathtaking.

Enjoy.

Saturday, November 21, 2015

The 48 Laws of Power, #15: Crush Your Enemy Totally

One of my favorite books on strategy is The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene and

Joost Elffers. Where The Art of War, by Sun Tzu is written as an

overview of the whole topic of strategy, seeking to provide an overall

understanding of the subject; and The 36 Strategies tries to impart the

knack of strategic thinking through 36 maxims related to well known

Chinese folk stories, Mr. Greene focuses on how we influence and

manipulate one another, ie "power".

Mr. Greene draws from both Eastern and Western history and literature as his source material. Sun Tzu and Machiavelli as cited as much as wonderful stories of famous con men. Among my favorites is about a scrap metal dealer thinking he bought the Eiffel Tower.

Each of the 48 Laws carries many examples, along with counter examples where it is appropriate that they be noted, and even reversals.

It is a very thorough study of the subject and the hardback version is beautifully produced.

One of the things I admire about Greene is that he not only studied strategy, he applied what he learned to his own situation and prospered.

All great leaders since Moses have known that a feared enemy must be crushed completely. Sometimes they have learned this the hard way. If one ember is left alight, no matter how dimly it smolders, a fire will eventually break out. More is lost through stopping halfway than through total annihilation. The enemy will recover, and will seek revenge. Crush him, not only in body but in spirit.

Mr. Greene draws from both Eastern and Western history and literature as his source material. Sun Tzu and Machiavelli as cited as much as wonderful stories of famous con men. Among my favorites is about a scrap metal dealer thinking he bought the Eiffel Tower.

Each of the 48 Laws carries many examples, along with counter examples where it is appropriate that they be noted, and even reversals.

It is a very thorough study of the subject and the hardback version is beautifully produced.

One of the things I admire about Greene is that he not only studied strategy, he applied what he learned to his own situation and prospered.

All great leaders since Moses have known that a feared enemy must be crushed completely. Sometimes they have learned this the hard way. If one ember is left alight, no matter how dimly it smolders, a fire will eventually break out. More is lost through stopping halfway than through total annihilation. The enemy will recover, and will seek revenge. Crush him, not only in body but in spirit.

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

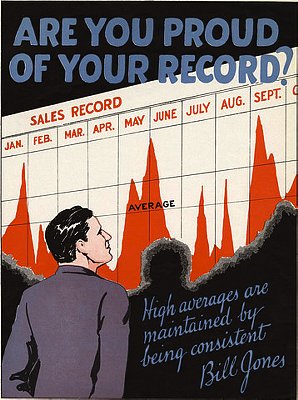

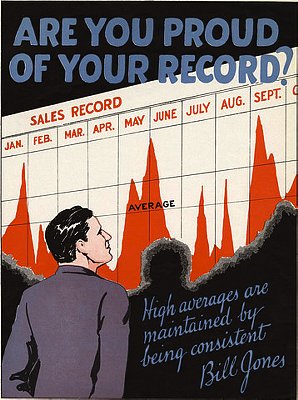

Improve Your Martial Arts Practice Every Day

Below is an excerpt from another excellent article at The Art of Manliness. The full article may be read here.

Brett and Kate McKay

It’s happened to all of

us.

You have a “come to Jesus” moment and decide you need to make changes in

your life. Maybe you need to drop a few pounds (or more), want to pay

off some debt, or desperately long to quit wasting time on the internet.

So you start planning and scheming.

You take to your journal and write out a bold strategy on how you’re

going to tackle your quest for self-improvement. You set big, hairy

SMART goals with firm deadlines. You download the apps and buy the gear

that will help you reach your objectives.

You feel that telltale rush that comes with believing you’re turning

over a new leaf, and indeed, the first few days go great. “This time,”

you tell yourself, “this time is different.”

But then…

You had a long day at work, you just can’t make it to the gym, and by

golly, eating an entire pizza would really make you feel better.

Or an unexpected expense comes up, and your bank account dips back into

the red.

Or you decide you’ve been doing really well with being focused, so

what’s a few minutes of aimless web surfing going to do?

Within a matter of days, your fiery ambition to change yourself is

extinguished. That audacious, airtight plan in your journal? You don’t

even look at it again because along with your goal to lose weight, your

daily journaling goal has also met an untimely demise.

And so you’re back to where you started, only even worse off than

before. Because now you’re not just an overweight, in debt, and easily

distracted man, you’re an overweight, in debt, and easily distracted man

who has failed at not being overweight, in debt, or easily distracted.

The sting of failure can feel like an existential gut punch.

But time heals all wounds. Nature has — for better and worse — blessed

us with terrible memories, so we forget how crappy we felt when we

failed in our last attempt to radically improve ourselves.

Thus, six months later that itch to change yourself returns, and the

whole scenario plays itself out again, like some Napoleon Hill, Think

and Grow Rich-infused version of Groundhog Day.

Getting Off the Roller Coaster of Personal Development

Our quest to become better often feels like a roller coaster ride with

its proverbial ups and downs. By the time you’re headed down

Self-Improvement Mountain for the twentieth time, you’re vomiting out

the side of your cart in self-disgust, cursing yourself that you once

again bought a ticket to ride.

Why are our attempts to better ourselves usually so uneven, and why do

they so frequently end in failure? There are a few reasons:

Focusing on the big goal overwhelms us into inaction. It’s an article of

faith in the world of personal development that you have to make big,

Empire State goals. You don’t just want to dominate in your own life —

you want to dominate the world.

And so you draw up plans for leaving behind the 99% of schmos out there,

and becoming part of the extraordinary 1% — not necessarily as measured

in pure wealth, but in passion, fitness, financial independence, and

number of Machu Picchu pics in your Instagram feed.

But the enormity of your goals ends up overwhelming you into inaction.

What we moderns call “stress” would be better termed “fear”; the

physiological reaction is the same in both emotions. A big, audacious

goal looks to the brain just like a saber-toothed tiger stalking us in

the woods, and the idea of paying off $100K in student loan debt seems

so impossible that it’s actually scary. And when our brain encounters

scary, the old amygdala kicks into fight-flight-freeze mode, and you

assume the position of deer-stuck-in-headlights.

Big, giant goals can be awe-inspiring. But like many awe-inspiring

things — a lion, a black hole, the Grand Canyon — they can also swallow

you whole.

We think a magic bullet will save us. Let’s say that we’re able to

overcome the torpor-inducing effects of aiming for radical personal

change, and we start taking action towards achieving our goals. As

humans are wont to do, instead of just getting right to work doing the

boring, mundane, time-tested things that will bring success, we

typically start looking for “hacks” that will get us the results we want

as fast as possible and with as little work as possible. We want that

magic bullet that will allow us to hit our target right in the bulls-eye

with just one shot.

The danger of looking for a magic bullet is that you end up spending all

your time searching for it instead of actually doing the work that

needs to be done. You scroll through countless blog articles on

productivity, in hopes of discovering that one tip that will make you

superhumanly efficient. You listen to podcast after podcast from people

who earn their living telling people how to make money online, hoping

one day you’ll hear an insight that will unlock your businesses’

potential, so you too can make your living online, telling other people

how to make a living online. You research and find the perfect gratitude

journal so you can be more zen.

The insidious thing about searching for magic bullets is that you feel

like you’re doing something to reach your goals when in fact you’re

doing nothing. Magic bullet hunting is masturbatory self-improvement.

All the pleasure, without the production of metaphorical progeny. Read

more at: http://tr.im/W5Flm

| Get 1% Better Every Day: The Kaizen Way to Self-Improvement |

It’s happened to all of us.

You have a “come to Jesus” moment and decide you need to make changes in your life. Maybe you need to drop a few pounds (or more), want to pay off some debt, or desperately long to quit wasting time on the internet.

So you start planning and scheming.

You

take to your journal and write out a bold strategy on how you’re going

to tackle your quest for self-improvement. You set big, hairy SMART goals with firm deadlines. You download the apps and buy the gear that will help you reach your objectives.

You

feel that telltale rush that comes with believing you’re turning over a

new leaf, and indeed, the first few days go great. “This time,” you

tell yourself, “this time is different.”

But then…

You

had a long day at work, you just can’t make it to the gym, and by

golly, eating an entire pizza would really make you feel better.

Or an unexpected expense comes up, and your bank account dips back into the red.

Or you decide you’ve been doing really well with being focused, so what’s a few minutes of aimless web surfing going to do?

Within

a matter of days, your fiery ambition to change yourself is

extinguished. That audacious, airtight plan in your journal? You don’t

even look at it again because along with your goal to lose weight, your

daily journaling goal has also met an untimely demise.

And

so you’re back to where you started, only even worse off than before.

Because now you’re not just an overweight, in debt, and easily

distracted man, you’re an overweight, in debt, and easily distracted man

who has failed at not being overweight, in debt, or easily distracted. The sting of failure can feel like an existential gut punch.

But

time heals all wounds. Nature has — for better and worse — blessed us

with terrible memories, so we forget how crappy we felt when we failed

in our last attempt to radically improve ourselves.

Thus,

six months later that itch to change yourself returns, and the whole

scenario plays itself out again, like some Napoleon Hill, Think and Grow Rich-infused version of Groundhog Day.

Getting Off the Roller Coaster of Personal Development

Our

quest to become better often feels like a roller coaster ride with its

proverbial ups and downs. By the time you’re headed down

Self-Improvement Mountain for the twentieth time, you’re vomiting out

the side of your cart in self-disgust, cursing yourself that you once

again bought a ticket to ride.

Why

are our attempts to better ourselves usually so uneven, and why do they

so frequently end in failure? There are a few reasons:

Focusing on the big goal overwhelms us into inaction.

It’s an article of faith in the world of personal development that you

have to make big, Empire State goals. You don’t just want to dominate in

your own life — you want to dominate the world.

And

so you draw up plans for leaving behind the 99% of schmos out there,

and becoming part of the extraordinary 1% — not necessarily as measured

in pure wealth, but in passion, fitness, financial independence, and

number of Machu Picchu pics in your Instagram feed.

But

the enormity of your goals ends up overwhelming you into inaction. What

we moderns call “stress” would be better termed “fear”; the

physiological reaction is the same in both emotions. A big, audacious

goal looks to the brain just like a saber-toothed tiger stalking us in

the woods, and the idea of paying off $100K in student loan debt

seems so impossible that it’s actually scary. And when our brain

encounters scary, the old amygdala kicks into fight-flight-freeze mode,

and you assume the position of deer-stuck-in-headlights.

Big,

giant goals can be awe-inspiring. But like many awe-inspiring things — a

lion, a black hole, the Grand Canyon — they can also swallow you whole.

We think a magic bullet will save us.

Let’s say that we’re able to overcome the torpor-inducing effects of

aiming for radical personal change, and we start taking action towards

achieving our goals. As humans are wont to do, instead of just getting

right to work doing the boring, mundane, time-tested things that will

bring success, we typically start looking for “hacks” that will get us

the results we want as fast as possible and with as little work as

possible. We want that magic bullet that will allow us to hit our target

right in the bulls-eye with just one shot.

The danger of looking for a magic bullet

is that you end up spending all your time searching for it instead of

actually doing the work that needs to be done. You scroll through

countless blog articles on productivity, in hopes of discovering that

one tip that will make you superhumanly efficient. You listen to podcast

after podcast from people who earn their living telling people how to

make money online, hoping one day you’ll hear an insight that will

unlock your businesses’ potential, so you too can make your living

online, telling other people how to make a living online. You research

and find the perfect gratitude journal so you can be more zen.

The

insidious thing about searching for magic bullets is that you feel like

you’re doing something to reach your goals when in fact you’re doing nothing. Magic bullet hunting is masturbatory self-improvement. All the pleasure, without the production of metaphorical progeny.

We stop doing the things that helped us improve in the first place. Okay. So let’s say you don’t let the bigness of your goal overwhelm you, and you’re not a chump magic bullet hunter either.

You

get to work. Slowly but surely you start seeing results. You lose five

pounds. You whittle $200 off your debt. You meditate for 20 minutes a

day for a whole week.

You’re having success!

But

in our personal backslapping, we would do well to heed Napoleon’s

warning: “The greatest danger occurs at the moment of victory.”

There’s

a tendency for folks to view self-improvement as a destination. They

think that once you reach your goal, you’re done. You can take it easy.

So when these folks start having some success and things start getting

better in their lives, they stop doing the things that got them to that

point. And so they start backsliding.

I fell into this trap when I was first trying to get a handle on my depression.

I’d take some proactive steps to leash my black dog — meditate, write

in my journal, get outside, etc. As soon as I started to feel better,

I’d think, “Hey! I beat it this time! I’m cured!” So I let up. I stopped

doing the things that helped me feel better in the first place. And of

course, I went back to feeling terrible.

Self-improvement

isn’t a destination. You’re never done. Even if you have some success,

if you want to maintain it, you have to keep doing the things you were

doing that got you that success in the first place.

The Kaizen Effect: Get 1% Better Each Day

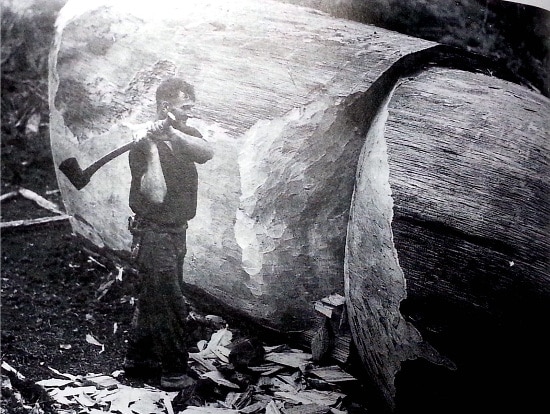

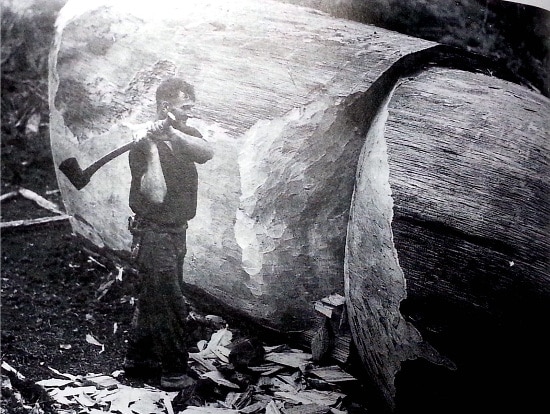

“Little strokes fell great oaks.” –Benjamin Franklin

It’s time to get off the self-improvement roller coaster.

To do so, we’re going to embrace the philosophy of small, continuous improvement.

It’s called Kaizen. It sounds like a mystical Japanese philosophy passed down by wise, bearded sages who lived in secret caves.

The

reality is that it was developed by Depression-era American business

management theorists in order to build the arsenal of democracy that

helped the U.S. win World War II. Instead of telling companies to make

radical, drastic changes to their business infrastructure and processes,

these management theorists exhorted them to make continuous

improvements in small ways. A manual created by the U.S. government to

help companies implement this business philosophy urged factory

supervisors to “look for hundreds of small things you can improve. Don’t

try to plan a whole new department layout — or go after a big

installation of new equipment. There isn’t time for these major items.

Look for improvements on existing jobs with your present equipment.”

After

America and its allies had defeated Japan and Germany with the weaponry

produced by plants using the small, continuous improvement philosophy,

America introduced the concept to Japanese factories to help revitalize

their economy. The Japanese took to the idea of small, continual

improvement right away and gave it a name: Kaizen — Japanese for continuous improvement.

While

Japanese companies embraced this American idea of small, continuous

improvement, American companies, in an act of collective amnesia, forgot

all about it. Instead, “radical innovation” became the watchword in

American business. Using Kaizen, Japanese auto companies like Toyota

slowly but surely began to outperform American automakers during the

1970s and 1980s. In response, American companies started asking Japanese

companies to teach them about a business philosophy American companies

had originally taught the Japanese. Go figure.

It’s happened to all of

us.

You have a “come to Jesus” moment and decide you need to make changes in

your life. Maybe you need to drop a few pounds (or more), want to pay

off some debt, or desperately long to quit wasting time on the internet.

So you start planning and scheming.

You take to your journal and write out a bold strategy on how you’re

going to tackle your quest for self-improvement. You set big, hairy

SMART goals with firm deadlines. You download the apps and buy the gear

that will help you reach your objectives.

You feel that telltale rush that comes with believing you’re turning

over a new leaf, and indeed, the first few days go great. “This time,”

you tell yourself, “this time is different.”

But then…

You had a long day at work, you just can’t make it to the gym, and by

golly, eating an entire pizza would really make you feel better.

Or an unexpected expense comes up, and your bank account dips back into

the red.

Or you decide you’ve been doing really well with being focused, so

what’s a few minutes of aimless web surfing going to do?

Within a matter of days, your fiery ambition to change yourself is

extinguished. That audacious, airtight plan in your journal? You don’t

even look at it again because along with your goal to lose weight, your

daily journaling goal has also met an untimely demise.

And so you’re back to where you started, only even worse off than

before. Because now you’re not just an overweight, in debt, and easily

distracted man, you’re an overweight, in debt, and easily distracted man

who has failed at not being overweight, in debt, or easily distracted.

The sting of failure can feel like an existential gut punch.

But time heals all wounds. Nature has — for better and worse — blessed

us with terrible memories, so we forget how crappy we felt when we

failed in our last attempt to radically improve ourselves.

Thus, six months later that itch to change yourself returns, and the

whole scenario plays itself out again, like some Napoleon Hill, Think

and Grow Rich-infused version of Groundhog Day.

Getting Off the Roller Coaster of Personal Development

Our quest to become better often feels like a roller coaster ride with

its proverbial ups and downs. By the time you’re headed down

Self-Improvement Mountain for the twentieth time, you’re vomiting out

the side of your cart in self-disgust, cursing yourself that you once

again bought a ticket to ride.

Why are our attempts to better ourselves usually so uneven, and why do

they so frequently end in failure? There are a few reasons:

Focusing on the big goal overwhelms us into inaction. It’s an article of

faith in the world of personal development that you have to make big,

Empire State goals. You don’t just want to dominate in your own life —

you want to dominate the world.

And so you draw up plans for leaving behind the 99% of schmos out there,

and becoming part of the extraordinary 1% — not necessarily as measured

in pure wealth, but in passion, fitness, financial independence, and

number of Machu Picchu pics in your Instagram feed.

But the enormity of your goals ends up overwhelming you into inaction.

What we moderns call “stress” would be better termed “fear”; the

physiological reaction is the same in both emotions. A big, audacious

goal looks to the brain just like a saber-toothed tiger stalking us in

the woods, and the idea of paying off $100K in student loan debt seems

so impossible that it’s actually scary. And when our brain encounters

scary, the old amygdala kicks into fight-flight-freeze mode, and you

assume the position of deer-stuck-in-headlights.

Big, giant goals can be awe-inspiring. But like many awe-inspiring

things — a lion, a black hole, the Grand Canyon — they can also swallow

you whole.

We think a magic bullet will save us. Let’s say that we’re able to

overcome the torpor-inducing effects of aiming for radical personal

change, and we start taking action towards achieving our goals. As

humans are wont to do, instead of just getting right to work doing the

boring, mundane, time-tested things that will bring success, we

typically start looking for “hacks” that will get us the results we want

as fast as possible and with as little work as possible. We want that

magic bullet that will allow us to hit our target right in the bulls-eye

with just one shot.

The danger of looking for a magic bullet is that you end up spending all

your time searching for it instead of actually doing the work that

needs to be done. You scroll through countless blog articles on

productivity, in hopes of discovering that one tip that will make you

superhumanly efficient. You listen to podcast after podcast from people

who earn their living telling people how to make money online, hoping

one day you’ll hear an insight that will unlock your businesses’

potential, so you too can make your living online, telling other people

how to make a living online. You research and find the perfect gratitude

journal so you can be more zen.

The insidious thing about searching for magic bullets is that you feel

like you’re doing something to reach your goals when in fact you’re

doing nothing. Magic bullet hunting is masturbatory self-improvement.

All the pleasure, without the production of metaphorical progeny. Read

more at: http://tr.im/W5Flm

It’s happened to all of

us.

You have a “come to Jesus” moment and decide you need to make changes in

your life. Maybe you need to drop a few pounds (or more), want to pay

off some debt, or desperately long to quit wasting time on the internet.

So you start planning and scheming.

You take to your journal and write out a bold strategy on how you’re

going to tackle your quest for self-improvement. You set big, hairy

SMART goals with firm deadlines. You download the apps and buy the gear

that will help you reach your objectives.

You feel that telltale rush that comes with believing you’re turning

over a new leaf, and indeed, the first few days go great. “This time,”

you tell yourself, “this time is different.”

But then…

You had a long day at work, you just can’t make it to the gym, and by

golly, eating an entire pizza would really make you feel better.

Or an unexpected expense comes up, and your bank account dips back into

the red.

Or you decide you’ve been doing really well with being focused, so

what’s a few minutes of aimless web surfing going to do?

Within a matter of days, your fiery ambition to change yourself is

extinguished. That audacious, airtight plan in your journal? You don’t

even look at it again because along with your goal to lose weight, your

daily journaling goal has also met an untimely demise.

And so you’re back to where you started, only even worse off than

before. Because now you’re not just an overweight, in debt, and easily

distracted man, you’re an overweight, in debt, and easily distracted man

who has failed at not being overweight, in debt, or easily distracted.

The sting of failure can feel like an existential gut punch.

But time heals all wounds. Nature has — for better and worse — blessed

us with terrible memories, so we forget how crappy we felt when we

failed in our last attempt to radically improve ourselves.

Thus, six months later that itch to change yourself returns, and the

whole scenario plays itself out again, like some Napoleon Hill, Think

and Grow Rich-infused version of Groundhog Day.

Getting Off the Roller Coaster of Personal Development

Our quest to become better often feels like a roller coaster ride with

its proverbial ups and downs. By the time you’re headed down

Self-Improvement Mountain for the twentieth time, you’re vomiting out

the side of your cart in self-disgust, cursing yourself that you once

again bought a ticket to ride.

Why are our attempts to better ourselves usually so uneven, and why do

they so frequently end in failure? There are a few reasons:

Focusing on the big goal overwhelms us into inaction. It’s an article of

faith in the world of personal development that you have to make big,

Empire State goals. You don’t just want to dominate in your own life —

you want to dominate the world.

And so you draw up plans for leaving behind the 99% of schmos out there,

and becoming part of the extraordinary 1% — not necessarily as measured

in pure wealth, but in passion, fitness, financial independence, and

number of Machu Picchu pics in your Instagram feed.

But the enormity of your goals ends up overwhelming you into inaction.

What we moderns call “stress” would be better termed “fear”; the

physiological reaction is the same in both emotions. A big, audacious

goal looks to the brain just like a saber-toothed tiger stalking us in

the woods, and the idea of paying off $100K in student loan debt seems

so impossible that it’s actually scary. And when our brain encounters

scary, the old amygdala kicks into fight-flight-freeze mode, and you

assume the position of deer-stuck-in-headlights.

Big, giant goals can be awe-inspiring. But like many awe-inspiring

things — a lion, a black hole, the Grand Canyon — they can also swallow

you whole.

We think a magic bullet will save us. Let’s say that we’re able to

overcome the torpor-inducing effects of aiming for radical personal

change, and we start taking action towards achieving our goals. As

humans are wont to do, instead of just getting right to work doing the

boring, mundane, time-tested things that will bring success, we

typically start looking for “hacks” that will get us the results we want

as fast as possible and with as little work as possible. We want that

magic bullet that will allow us to hit our target right in the bulls-eye

with just one shot.

The danger of looking for a magic bullet is that you end up spending all

your time searching for it instead of actually doing the work that

needs to be done. You scroll through countless blog articles on

productivity, in hopes of discovering that one tip that will make you

superhumanly efficient. You listen to podcast after podcast from people

who earn their living telling people how to make money online, hoping

one day you’ll hear an insight that will unlock your businesses’

potential, so you too can make your living online, telling other people

how to make a living online. You research and find the perfect gratitude

journal so you can be more zen.

The insidious thing about searching for magic bullets is that you feel

like you’re doing something to reach your goals when in fact you’re

doing nothing. Magic bullet hunting is masturbatory self-improvement.

All the pleasure, without the production of metaphorical progeny. Read

more at: http://tr.im/W5Flm

Sunday, November 15, 2015

The Birth of Tomiki Aikido

Kenji Tomiki was a giant in the martial arts of Japan. He was a high ranking student of both Judo's Jigoro Kano and Aikido's Morehei Ueshiba. The following article appeared in the Aikido Journal and was written by one of the first members of one of the first university aikido clubs, which gave birth to Tomiki Aikido. The full post may be read here. Enjoy.

First of all, I would like to explain how, where and why Tomiki Aikido started. It goes back to the month of April, 1958 when Waseda University approved our Aikido Club as an officially sanctioned sport club (called “Undo Bu” in Japanese), while no other universities recognized any Aikido clubs as such. Instead, all other Aikido clubs were called “Doko-Kai”, meaning a loosely organized club made up with people of the same interest. These unsanctioned sport clubs had neither the prestige nor the status of other sanctioned clubs such as Judo, Kendo, Karate, baseball, soccer, and other major sport clubs.

Prior to April, 1958, there was no Aikido club, even at Waseda University. Professor Kenji Tomiki was the Judo instructor and he taught Aikido to some members of the Waseda Judo Club before or after Judo practice. Obviously this arrangement had many limitations for developing truly well-trained Aikidokas.

I was very fortunate to be a freshman in this historical year of 1958. the Japanese school year begins in April, so that I could receive Professor Tomiki’s instructions from the club’s first day as a fully sanctioned sport club and benefit from his burning desire and profound vision of making Aikido the same as Judo, Kendo, and Karate.

One of the strict requirements attached to this official recognition by Waseda University was a stipulation of being able to measure and/or judge the progress and ability of Aikido students. In other words, any clubs belonging to the official Athletic Association must have competition of some fashion. This prerequisite was most welcome by Professor Tomiki, who had his dream to make Aikido as competitive and as internationally popular as Judo. From the very inception, he had his vision to create the method of Randori-Ho (free sparring practice) by combining the superb Aikido techniques taught by Osensei Morihei Ueshiba and the scientifically ideal educational doctrines taught by Professor Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo (which means “Gentle Way”). Professor Tomiki frequently told us how fortunate he was to receive direct training from these two extremely talented teachers. He said, “I learned the true meaning of really profound martial skills and techniques from Ueshiba-Sensei and I learned the doctrines, innovations and educational merits from Kano-Sensei”.

Thursday, November 12, 2015

Book Review: Chanpuru, Thoughts and Reflections from the Dojo

A new book from Tambuli Media is Chanpuru, Thoughts and Reflections from the Dojo by Garry Parker.

Mr. Parker describes his arrival in Okinawa as a young man as a part of his military service and his subsequent training under Takamiyagi Sensei in traditional, old style Okinawan karate.

What young man hasn't dreamed of training intensively under a master teacher for a number of years? Mr. Parker certainly was able to live that dream. He trained under Takamiyagi Sensei directly for some six years, before he returned to the US.

Once back in his native Georgia, he was unable to find any form of karate training that resembled in any way the traditional training he enjoyed in Okinawa, so at the urging of his teacher, he opened his own dojo.

One of the unexpected consequences was that he became acquainted with others who were in basically the same boat; having tasted the real thing in Okinawa or Japan, individuals who either trained alone or in small groups.

Parker returned to Okinawa regularly for intensive personal training under his teacher and so advanced his own skills.

To celebrate the 15th anniversary of the opening of his dojo Takamiyagi Sensei came to Georgia to take part and visit. Parker's students had a chance to experience some of that authentic taste, direct from source as well.

The book also includes many short pieces by Parker on a wide variety of subjects that are related to his karate training.

I found this to be a most pleasurable read and I would recommend it to anyone.

Mr. Parker describes his arrival in Okinawa as a young man as a part of his military service and his subsequent training under Takamiyagi Sensei in traditional, old style Okinawan karate.

What young man hasn't dreamed of training intensively under a master teacher for a number of years? Mr. Parker certainly was able to live that dream. He trained under Takamiyagi Sensei directly for some six years, before he returned to the US.

Once back in his native Georgia, he was unable to find any form of karate training that resembled in any way the traditional training he enjoyed in Okinawa, so at the urging of his teacher, he opened his own dojo.

One of the unexpected consequences was that he became acquainted with others who were in basically the same boat; having tasted the real thing in Okinawa or Japan, individuals who either trained alone or in small groups.

Parker returned to Okinawa regularly for intensive personal training under his teacher and so advanced his own skills.

To celebrate the 15th anniversary of the opening of his dojo Takamiyagi Sensei came to Georgia to take part and visit. Parker's students had a chance to experience some of that authentic taste, direct from source as well.

The book also includes many short pieces by Parker on a wide variety of subjects that are related to his karate training.

I found this to be a most pleasurable read and I would recommend it to anyone.

Monday, November 09, 2015

The First American Martial Arts Film Stars

Over at Kung Fu Tea, there is an interesting article on martial arts themed mainstream American films from the 30's and 40's. The first American martial arts film stars were James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn!

An excerpt is below. The full article, with many entertaining film clips, may be read here.

Introduction

Upon the gracious invitation from Dr. Judkins, I thought about what I could add to a historical perspective on the martial arts. After considering various topic ideas, I settled on the topic of martial arts in the context of American cinema, in particular the classical Hollywood cinema. In academic film studies, classical Hollywood cinema refers to the period of time from the late-1920s/early-1930s (when synchronized sound replaced the practices of silent filmmaking) to the late-1950s/early-1960s (when the fallout from the infamous 1948 Supreme Court case known as the “Paramount Decree” led to changes in the way films were produced, distributed, and exhibited). At this time Hollywood studios controlled all aspects of the filmmaking process and these efforts were conducted in accordance with a standardized “mode of production” (the standard academic text on this period remains The Classical Hollywood Cinema by David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson).

This was the era of Gone with the Wind, Casablanca, It’s a Wonderful Life, Singin’ in the Rain, and 12 Angry Men. It was also the era of ‘G’ Men, Behind the Rising Sun, Blood on the Sun, Tokyo Joe, and Pat and Mike. If most people haven’t heard of the films on the second list, that’s to be expected.

They haven’t been canonized in the academic literature nor have they managed to secure a place in the popular cultural imagination. The history of cinema has for the most part lost track of these films, while the history of martial arts cinema has yet to even recognize them, but thanks to TV, DVDs, and the Internet, history is always a mouse click or channel change away from being (re)discovered.

In typical historical accounts of martial arts cinema, Hollywood tends to be either ignored or denunciated on the basis of a confirmation bias which precludes the possibility of there being an American inheritance of cinematic martial arts. In the first issue of the Martial Arts Studies journal, I will attempt to counter a number of theoretical claims against American cinematic representations of the martial arts throughout Hollywood history, but here, I would like to show on historical grounds that there is, indeed, an American inheritance of cinematic martial arts with a lineage that can be traced back nearly a century through a number of intriguing and ambitious films

An excerpt is below. The full article, with many entertaining film clips, may be read here.

Introduction

Upon the gracious invitation from Dr. Judkins, I thought about what I could add to a historical perspective on the martial arts. After considering various topic ideas, I settled on the topic of martial arts in the context of American cinema, in particular the classical Hollywood cinema. In academic film studies, classical Hollywood cinema refers to the period of time from the late-1920s/early-1930s (when synchronized sound replaced the practices of silent filmmaking) to the late-1950s/early-1960s (when the fallout from the infamous 1948 Supreme Court case known as the “Paramount Decree” led to changes in the way films were produced, distributed, and exhibited). At this time Hollywood studios controlled all aspects of the filmmaking process and these efforts were conducted in accordance with a standardized “mode of production” (the standard academic text on this period remains The Classical Hollywood Cinema by David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson).

This was the era of Gone with the Wind, Casablanca, It’s a Wonderful Life, Singin’ in the Rain, and 12 Angry Men. It was also the era of ‘G’ Men, Behind the Rising Sun, Blood on the Sun, Tokyo Joe, and Pat and Mike. If most people haven’t heard of the films on the second list, that’s to be expected.

They haven’t been canonized in the academic literature nor have they managed to secure a place in the popular cultural imagination. The history of cinema has for the most part lost track of these films, while the history of martial arts cinema has yet to even recognize them, but thanks to TV, DVDs, and the Internet, history is always a mouse click or channel change away from being (re)discovered.

In typical historical accounts of martial arts cinema, Hollywood tends to be either ignored or denunciated on the basis of a confirmation bias which precludes the possibility of there being an American inheritance of cinematic martial arts. In the first issue of the Martial Arts Studies journal, I will attempt to counter a number of theoretical claims against American cinematic representations of the martial arts throughout Hollywood history, but here, I would like to show on historical grounds that there is, indeed, an American inheritance of cinematic martial arts with a lineage that can be traced back nearly a century through a number of intriguing and ambitious films

Friday, November 06, 2015

Kimura's Training Routine

Below is an excerpt from an article that appeared at BJJ Eastern Europe describing Masahiko Kimura's training routine. He was an off the charts martial artist and his training routine reflects that.

The full article may be read here. It is accompanied by several interesting videos. Check it out! Enjoy.

The full article may be read here. It is accompanied by several interesting videos. Check it out! Enjoy.

Masahiko Kimura)was a Japanese judoka who is widely considered one of the greatest judoka of all time. (5 ft 7in 170 cm; 85 kg, 187 lb) He was born on September 10, 1917 in Kumamoto, Japan. In submission grappling, the reverse ude-garami arm lock is often called the “Kimura”, due to his famous victory over Gracie jiu-jitsu developer Hélio Gracie.

Masahiko Kimura began training Judo at age of 9 and was promoted to yondan (4th dan) at the age of 15 after six years of Judo. He had defeated six opponents (who were all 3rd and 4th dan) in a row. In 1935 at age 18 he became the youngest ever godan (5th degree black belt) when he defeated eight consecutive opponents at Kodokan (headquarters for the main governing body of Judo).

Kimura’s remarkable success can in part be attributed to his fanatical training regimen, managed by his teacher, Tatsukuma Ushijima. Kimura reportedly lost only four judo matches in his lifetime, all occurring in 1935. He considered quitting judo after those losses, but through the encouragement of friends he began training again. He consistently practiced the leg throw osoto gari (large outer reap) against a tree. Daily randori or sparring sessions at Tokyo Police and Kodokan dojos resulted in numerous opponents suffering from concussions and losing consciousness. Many opponents asked Kimura not to use his osoto gari.

At the height of his career Kimura’s training involved a thousand push-ups and nine-hours practice every day. He was promoted to 7th dan at age 30, a rank that was frozen after disputes with Kodokan over becoming a professional wrestler, refusing to return the All Japan Judo Championship flag, and issuing dan ranks while in Brazil.

Mas Oyama himself said that the ONLY person who trained as hard as he did… or in-fact, harder than he did, was the one and only: Masahiko Kimura…

...

Masahiko Kimura’s Daily Training Regime (Kimura trained 6 days a week):

1,000 Push-ups or Hindu Push-ups

Bunny Hop- 1 km

Headstand- 3 x 3 Minutes (against a wall)

Judo Practice- 100 Throws

One-Arm Barbell Lift and Press- 15 Reps each side OR Bench Press- 3 Sets: 3, 2, and 1 Reps

200 Sit-ups off Partner’s Back or Decline Sit-ups

200 Squats with Partner/Log/Barbell/Sandbag (150-200lbs)

Judo Practice- 100 Drills Submissions

500 Shuto (Knife-hand Strikes)

Judo Practice- 100 Entries

Judo Randori- “X” x 3 Minute Rounds

Practice Throws (particularly Uchi-mata) Against a Tree- 1 Hour

Additional Judo Practice- 1 Hour

Bunny Hop- 1 km

Headstand- 3 x 3 Minutes (against a wall)

Judo Practice- 100 Throws

One-Arm Barbell Lift and Press- 15 Reps each side OR Bench Press- 3 Sets: 3, 2, and 1 Reps

200 Sit-ups off Partner’s Back or Decline Sit-ups

200 Squats with Partner/Log/Barbell/Sandbag (150-200lbs)

Judo Practice- 100 Drills Submissions

500 Shuto (Knife-hand Strikes)

Judo Practice- 100 Entries

Judo Randori- “X” x 3 Minute Rounds

Practice Throws (particularly Uchi-mata) Against a Tree- 1 Hour

Additional Judo Practice- 1 Hour