One of my favorite sets of books is the Asian Saga by James Clavell, consisting of Shogun, Tai-Pan, Gai-jin, King Rat, Noble House, and finally Whirlwind. Theses are remarkable works of historical fiction. What is most remarkable is how Clavell found real people and events in history from which to write these terrific novels.

The best known book in the serie is Shogun. The main character in Shogun is John Blackthorne, a 16th century Englishman who is ship wrecked in Japan just as the war to decide who will be Shogun is about to break out.

The character of John Blackthorne is based upon a real Englishman who was indeed shipwrecked in Japan at that time. In my opinion though, the adventures of John Blackthorne pales in comparison to those of the historical figure, Will Adams.

If you click on the title of this post, you'll be directed to the page found by Answers.com, where there will be a more complete text, pictures, and more links.

William Adams

William Adams (September 24, 1564, May 16, 1620), also known in Japanese as Anjin-sama (謖蛾・讒・ anjin, "pilot"; sama, a Japanese social title) and Miura Anjin (荳画オヲ謖蛾・: "the pilot of Miura"), was an English navigator who went to Japan and is believed to be the first Briton ever to reach Japan.

Early life

William Adams was born at Gillingham, in Kent, England. After losing his father at the age of 12, he was apprenticed to shipyard owner Master Nicholas Diggins at Limehouse for the seafaring life. He spent the next 12 years learning shipbuilding, astronomy and navigation before entering the British navy. Adams served in the Royal Navy under Sir Francis Drake and saw naval service against the Spanish Armada in 1588 as master of the Richarde Dyffylde. Adams then became a pilot for the Barbary Company.

During this service, according to Jesuit sources, he took part in an expedition to the Arctic that lasted about two years in search of a Northeast Passage along the coast of Siberia to the Far East.

Expedition to the Far East

Attracted by the Dutch trade with India, Adams, then 34, shipped as pilot major with a five-ship fleet dispatched to the Far East in 1598 by a company of Rotterdam merchants (a voorcompagnie, anterior to the Dutch East India Company).

He set sail from Rotterdam in June 1598 on the Hoop and joined up with the rest of the fleet (Liefde, Geloof, Trouw and Blijde Boodschap ("Good Tiding", captained by Dirck Gerritz Pomp)) on June 24, under the command of Jacques Mahu. Originally, the fleet's mission was to sail for the west coast of Southern America, where they would sell their cargo for silver, and to head for Japan only if the first mission failed.

The vessels, boats ranging from 75 to 250 tons and crowded with men, were driven to the coast of Guinea (West-Africa) where the adventurers attacked the island of Annabon for supplies then moved on for the straits of Magellan. Scattered by stress of weather and after several disasters in the South Atlantic, only three ships out of five made it through the Magellan Straits.

During the voyage, Adams had changed ships to the Liefde (originally Erasmus because of the wooden figurehead of Erasmus on her bow). The Liefde waited for the other ships at Santa Maria Island off the Chilean coast. However, only the Hoop had arrived by the spring of 1599 and the captains of both vessels, together with Adams's brother Thomas and 20 other men, lost their lives in an encounter with the native Indians.

In fear of the Spaniards, the remaining crews determined to sail across the Pacific. It was late November 1599 when the two ships sailed westwardly for Japan. On their way, the two ships made landfall in "certain islands" (possibly the islands of Hawaii) where eight sailors deserted the ships.

Later during the voyage, a typhoon claimed the Hoop with all souls in late February 1600.

Arrival in Japan

In April 1600, after more than nineteen months at sea, the Liefde with a crew of about twenty sick and dying men (out of an initial crew of about one hundred) was brought to anchor off the island of Kyushu, Japan. When the nine crew members strong enough to stand made landfall on April 19 off Bungo (present-day Usuki, Oita Prefecture), they were met by natives and Portuguese Jesuit priests claiming that Adams' ship was a pirate vessel and that the crew should be crucified as pirates.

The ship was seized and the sickly crew was imprisoned at Osaka Castle on orders by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the daimyo of Mikawa and future Shogun. The 19 bronze cannons of the Liefde were unloaded and according to Spanish accounts later employed at the decisive battle of Sekigahara in October 21, 1600.

Adams met Ieyasu in Osaka three times between May and June 1600. He was questioned by Ieyasu, then a guardian of the young son of the Taiko (Toyotomi Hideyoshi), the ruler who had just died. Adams' knowledge of ships, shipbuilding and nautical smattering of mathematics appealed to Ieyasu.

Ieyasu ordered the crew to sail the Liefde from Bungo to Edo where, rotten and beyond repair, she later sank. Japan's first western-style sailing shipsIn 1604, Ieyasu ordered Adams and his companions to build a western-style sailing ship at Ito on the east coast of the Izu Peninsula. An 80-ton vessel was completed and the Shogun ordered a larger ship, 120 tons, to be built the following year (both were slightly smaller than the Liefde, which was 150 tons).

According to Adams, Ieyasu "came aboard to see it, and the sight whereof gave him great content". In 1610, the 120 ton ship (later named San Buena Ventura) was lent to shipwrecked Spanish sailors, who sailed back to Mexico with it, accompanied by a mission of 22 Japanese.

Following the construction, Ieyasu invited Adams to visit his palace whenever he liked and "that always I must come in his presence" (Letters).

Other survivors of the Liefde were also rewarded with favours and even allowed to pursue foreign trade. Most of the original crew were able to leave Japan in 1605 with the help of the daimyo of Hirado.

The first foreign samurai

The Shogun took a liking to Adams and made him a revered diplomatic and trade adviser and bestowed great privileges upon him. Ultimately, Adams became his personal advisor on all things related to Western powers and civilization and, after a few years, Adams replaced the Jesuit Padre Joan Rodriguez as the Shogun's official interpreter. Padre Valentim Carvalho wrote: "After he had learned the language, he had access to Ieyasu and entered the palace at any time"; he also described him as "a great engineer and mathematician".

Adams had a wife and children in England but Ieyasu had forbidden the Englishman to leave Japan. He was presented with two swords representing the authority of a Samurai. The Shogun decreed that William Adams the pilot was dead and that Miura Anjin (荳画オヲ謖蛾・), a samurai, was born.

This made Adams's wife in England in effect a widow (although Adams managed to send regular support payments to her after 1613 via the English and Dutch companies) and "freed" Adams to serve the Shogunate on a permanent basis. Adams also received the title of hatamoto (bannerman), a high-prestige position as a direct retainer in the Shogun's court. He was provided with generous revenues: "For the services that I have done and do daily, being employed in the Emperor's service, the emperor has given me a living" (Letters).

He was granted a fief in Hemi (Jp: 騾ク隕・ within the boundaries of present-day Yokosuka City, "with eighty or ninety husbandmen, that be my slaves or servants" (Letters). His estate was valued at 250 koku (measure of the income of the land in rice equal to about five bushels). He finally wrote "God hath provided for me after my great misery" (Letters) by which he meant the disaster ridden voyage that had initially brought him to Japan.

Adams's estate was located next to the harbour of Uraga, the traditional point of entrance to Edo Bay where he is recorded to have dealt with the cargoes of foreign ships. Adams' position gave him the means to marry Oyuki, the daughter of Magome Kageyu, a highway official who was in charge of a packhorse exchange on one of the grand imperial roads that led out of Edo (roughly present day Tokyo).

Although Magome was important, he was not of noble birth, nor high social standing and so it was likely that Adams married out of true affection rather than for social reasons. Adams and Oyuki had a son called Joseph and a daughter named Susanna.

Adams had a high regard for Japan, its people, and its civilization: The people of this Land of Japan are good of nature, curteous above measure, and valiant in war: their justice is severely executed without any partiality upon transgressors of the law. They are governed in great civility. I mean, not a land better governed in the world by civil policy. The people be very superstitious in their religion, and are of divers opinions. (William Adam's letter to Bantam, 1612)

Estalishment of the Dutch East India Company in Japan

The Liefde's Captain, Jacob Quaeckernaeck, and the treasurer, Melchior van Santvoort, were also sent by Ieyasu in 1604 on a Shogun-licensed Red Seal Ship to Patani in Southeast Asia to contact the Dutch East India Company trading factory which had just been established there in 1602, to bring more western trade to Japan and break the Portuguese monopoly on Japan's external trade. In 1605, Adams obtained a letter from Ieyasu formally inviting the Dutch to trade with Japan.

Hampered by conflicts with the Portuguese and limited resources in Asia, the Dutch were not able to send ships until 1609. Two Dutch ships, commanded by Jacob Groenewegen, De Griffioen (the "Griffin", 19 canons) and Roode Leeuw met Pijlen (the "Red lion with arrows", 26 cannons), were finally sent from Holland and arrived in Japan on July 2nd, 1609. Once the Dutch ships arrived in the harbour of Hirado, Adams negotiated on their behalf with the Shogun and obtained free trading rights throughout Japan (in contrast, the Portuguese were only allowed to sell their goods in Nagasaki at fixed, negotiated prices) and to establish a trading factory there: The Hollanders be now settled (in Japan) and I have got them that privilege as the Spaniards and Portigals could never get in this 50 or 60 years in Japan. (William Adams letter to Bantam).

Following the obtaining of this trading right through an edict of Tokugawa Ieyasu on August 24th, 1609, the Dutch inaugurated a trading factory in Hirado on September 20th, 1609. The "trade pass" (Dutch: "Handelspas") was kept preciously by the Dutch in Hirado and then Dejima as a guarantee of their trading rights, during the following two centuries of their presence in Japan.

Religious rivalries

Adams, a Protestant, was seen as a rival by the Portuguese and Catholic religious orders in Japan. When he and his crew arrived on the 'Liefde', the Jesuits settled in Nagasaki became very anxious as they had informed the Japanese, innaccurately, that all Europe was united under a single, undisputed church. Because of the fear that Adams would shed light on the truth, the Jesuits conspired against him, asking forcefully for his crucifixion at first, then having him imprisoned when Ieyasu refused to kill Adams for no reason.

Later, after Adams' power had grown, the Jesuits attempted first to convert him, then offered to secretly bear him away from Japan on a Portuguese ship. The fact that the Jesuits were willing to disobey the orders set down by Ieyasu: that Adams may not leave Japan, betray the degree to which they feared his influence - for good reason.

Catholic priests insisted that he was using his influence on Ieyasu to discredit them: In his character of heretic, he constantly endeavoured to discredit our church as well as its ministers".. He and others "by false accusation ... have rendered our preachers such objects of suspicion that Ieyasu fears and readily believes that they are rather spies than sowers of the Holy Faith in his kingdoms. (Padre Valentim Carvalho).

Ieyasu, influenced by Adams' counsels and social trouble caused by the numerous catholic converts, expelled the Jesuits from Japan in 1614 and demanded the Japanese Catholics abandon their faith.

Adams also apparently warned Ieyasu against Spanish approaches explaining that they typically tried to establish Catholic converts and strongholds as a prelude to the arrival of conquistadores and full invasion of the country as they had done in the Philippines, Mexico and Peru in the previous hundred years.

Establishment of an English trading factory

In 1611, news came to Adams of an English settlement in Bantam, Indonesia and he sent a letter asking them to give news of him to his family and friends in England and enticing them to engage in trade with Japan which "the Hollanders have here an Indies of money" (Adams's letter to Bantam).

In 1613, the English Captain John Saris arrived at Hirado in the ship Clove with the intent of establishing a trading factory for the British East India Company (Hirado was already a trading post for the Dutch East India Company (the VOC)). Adams met with Saris's ire over his praise of Japan and adoption of Japanese customs: He persists in giving "admirable and affectionated commendations of Japan. It is generally thought amongst us that he is a naturalized Japaner." (John Saris)

In Hirado, Adams refused to stay in English quarters and instead resided with a local Japanese magistrate. It was also commented that he was wearing Japanese dress and spoke Japanese fluently.

Adams travelled with Saris to Shizuoka where they met with Ieyasu at his principal residence in September and then continued to Kamakura where they visited the famous Buddha (the 1252 Daibutsu on which the sailors etched their names) before moving on to Edo where they met Ieyasu's son Hidetada who was now nominally Shogun even though Ieyasu retained most of the actual decision making powers.

During that meeting, Hidetada gave Saris two varnished suits of armor for King James I, today housed in the Tower of London.

On their way back, they visited again Ieyasu who confered trading privileges to the British through a red-seal permit (Japanese: 譛ア蜊ー迥カ) giving them "free license to abide, buy, sell and barter" in Japan [2]. The English party headed back to Hirado on October 9, 1613. On this occasion, Adams asked for and obtained Ieyasu's authorization to return to his home country.

However, he ultimately declined Saris' offer to bring him back to England: "I answered him I had spent in this country many years, through which I was poor... [and] desirous to get something before my return". His true reasons seem to lie rather with his profound antipathy for Saris: "The reason I would not go with him was for diverse injuries done against me, the which were things to me very strange and unlooked for." (William Adams letters)

He accepted employment with the newly founded Hirado trading factory, signing a contract on November 24, 1613, becoming an employee of the East India Company for the yearly salary of 100 English Pounds, more than double the regular salary of 40 Pounds earned by the other factors at Hirado. Adams was to take a leading part, under Richard Cocks and together with six other compatriots, in the organization of this new English settlement.

During the ten year activity of the company between 1613 and 1623, apart from the first ship (the Clove in 1613), only three other English ships brought cargoes directly from London to Japan, invariably described as poor value on the Japanese market.

The only trade which helped support the factory was that organized between Japan and South-East Asia and mainly undertaken by Adams selling Chinese goods for Japanese silver: Were it not for hope of trade into China, or procuring some benefit from Siam, Pattania and Cochin China, it were no staying in Japon, yet it is certen here is silver enough & may be carried out at pleasure, but then we must bring them commodities to ther liking. (Richard Cocks Diary, 1617)

Character

After fifteen years spent in Japan, Adams' relations with his compatriots were not the easiest. He initially shunned the company of the newly arrived English sailors in 1613 and could not get on terms with Saris. However, Cocks, the head of the Hirado factory progressively came to appreciate Adams' character and distinctively Japanese self-control. In a letter to the East India Company: I find the man tractable and willing to do your worships the best service he may... I am persuaded I could live with him seven years before any extraordinary speeches should happen between us. (Cocks Diary)

Participation in Asian trade

The latter part of his life was spent in the service of the English trading company. He undertook a number of voyages to Siam in 1616 and Cochin China in 1617 and 1618, sometimes for the English East India Company, sometimes for his own account. He is recorded in Japanese sources as the owner of a Red Seal Ship of 500 tons.

Given the small number of ships coming from England (four ships in ten years: the Clove in 1613, the Hosiander in 1615, the Thomas and the Advice in 1616) and the poor value of their cargoes (broadcloth, knives, looking glasses, Indian cotton, etc.), William Adams played a key role in having the company partipate in the Red Seal system by obtaining trading certificates from the Shogun.

Altogether, seven junk voyages were made to Southeast Asia with mixed results including four of them headed by William Adams himself as Captain. Adams acknowledged God as his personal Provider before all people by renaming the ship, which he had acquired, with the phrase "Gift of God", the ship that he used for his expedition to Cochinchina.

1614 Siam expedition

In 1614, Adams wished to organize a trade expedition to Siam in hope of bolstering the factory's activities and cash situation. He bought for the factory and upgraded a 200-ton Japanese junk, renamed her the Sea Adventure, hired about 120 Japanese sailors and merchants as well as several Chinese traders, an Italian and a Castillan trader and the heavily laden ship left on November 1614, during the typhoon season. The merchants Richard Wickham and Edmund Sayers of the English factory's staff also participated to the voyage.

The ship was to purchase raw silk, Chinese goods, sappan wood, deer skins and ray skins (the latter used for the handles of Japanese swords), essentially carrying only silver (ツ」1250) and ツ」175 of merchandise (Indian cottons, Japanese weapons and lacquerware). The ship met with a typhoon near the Ryナォkyナォ Islands (modern Okinawa) and had to stop there to repair from 27 December 1614 until May 1615 before returning to Japan in June 1615 without having been able to complete any trade.

1615 Siam expedition

Adams again left Hirado in November 1615 for Ayutthaya in Siam on the refit Sea Adventure intent on bringing sappanwood for resale in Japan. Like the previous year, the cargo consisted mainly of silver (ツ」600) and also the Japanese and Indian goods unsold from the previous voyage. He managed to buy vast quantities of the profitable products, even buying two additional ships in Siam to transport everything.

Adams sailed the Sea Adventure back to Japan with 143 tonnes of sappanwood and 3700 deer skins, returning to Hirado in 47 days, (the whole trip lasting between 5 June and 22 July 1616). Sayers, on a hired Chinese junk, reached Hirado in October 1616 with 44 tons of sappanwood.

The third ship, a Japanese junk, brought 4,560 deer skins to Nagasaki in June 1617 after having missed the monsoon. Adams returned to Japan less than a week after the death of Ieyasu and accompanied Cocks and Eaton to court to offer presents to the new ruler Hidetada.

Although the death of Ieyasu in 1616 seems to have weakened Adams' political influence, Hidetada agreed to maintain the trading privileges of the English and issued a new Red Seal permit (Shuinjナ・ to Adams allowing him to continue trade activities overseas under the Shogun's protection. His position as hatamoto was also renewed.

On this occasion, Adams and Cocks also visited the Japanese Admiral Mukai Shogen Tadakatsu who lived near Adams' estate and they discussed plans about a possible invasion of the Catholic Philippines.

1617 Cochinchina expedition

In March 1617, Adams set sail for Cochinchina having purchased the junk Sayers had brought from Siam and renamed it the Gift of God. He intended to find two English factors that had left Hirado two years before to explore commercial opportunities (the first voyage to South East Asia by the Hirado English Factory). He returned to Japan with the knowledge that both had been killed and robbed of their silver.

1618 Cochinchina expedition

In 1618, Adams is recorded as having organized his last Red Seal trade expedition to Cochinchina and Tonkin (modern Vietnam), the last expedition of the English Hirado Factory to Southeast Asia. The ship, a chartered Chinese junk, left Hirado on 11 March 1618 but met with bad weather that forced it to stop at ナ茎hima in the northern Ryukyus. The ship sailed back to Hirado in May.

Those expeditions to Southeast Asia helped the English factory survive for some time (During that period, sappanwood resold in Japan with a 200% profit) until the factory fell into bankruptcy due to high expenditures.

Adams's legacy

Adams died at Hirado, north of Nagasaki, on May 16, 1620, aged 56 and was buried in his fief in Hemi, Yokosuka. The English factory was dissolved three years later due to its unprofitability.

In his will, he left his townhouse in Edo, his fief in Hemi, and 500 British pounds to be divided evenly between his family in England and his family in Japan. Cocks wrote: "I cannot but be sorrowfull for the loss of such a man as Capt William Adams, he having been in such favour with two Emperors of Japan as never any Christian in these part of the world" (Cocks's Diary)

Cocks remained in contact with Adams' family sending gifts and in March 1622, offering silks for Joseph and Susanna. He handed to Joseph his father's sword and dagger on the Christmas following Adams' death. Cocks also records that Hidetada transferred the lordship from William Adams to his son Joseph Adams with the attendant rights to the estate at Hemi: He (Hidetada) has confirmed the lordship to his son, which the other emperor (Ieyasu) gave to the father (Cocks's Dairy)

Cocks was also in charge of using Adams' trading rights (the shuinjナ・/a>) for the benefit of Adams' children, Joseph and Susanna, a task he performed conscientiously and which was handled by the Dutch after 1623.

Adams' son also kept the title of Miura Anjin and was a successful trader until the closure of the country in 1635 when he disappeared from historical records.

Adams's memory is preserved in the naming of a town in Edo (modern Tokyo), Anjin-chナ・(in modern-day Nihonbashi), where he had a house and by an annual celebration on June 15 in his honour. A village in his fiefdom, Anjinzuka (螳蛾・蝪・ "Burial mound of the Pilot"), in modern Yokosuka, bears his name. Also, in the city of Itナ・/a>, Shizuoka, the Miura Anjin Festival is held all day on August 10. Today, both Itナ・and Yokosuka are sister cities of Adams' birth town of Gillingham.

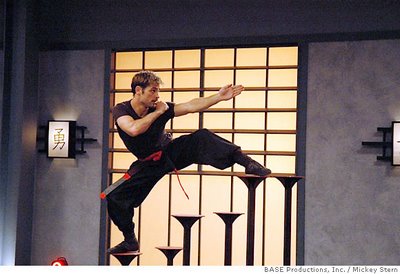

The life of William Adams also inspired James Clavell's Shogun which was a best-selling novel and then a celebrated TV miniseries. The fictional heroics of John Blackthorne were loosely based on Adams' adventures in the first few years after his arrival in Japan.

Famous William Adams quotes

Altogether, four letters of William Adams are known, among which the letter to his wife and the letter to the English trading post at Bantam are the most informative. Some other famous quotes:

· "Most of us are just about as happy as we make up our minds to be."

· "Faith is a continuation of reason."

· "As a nation of free men, we must live through all time, or die by suicide."