Thursday, June 30, 2005

Comments should be fixed.

The comments section was accidentally set for 'members ony.' It should be fixed now.

Imperial Tea site updated

Click on the title of this post to be directed to the updated website for the Imperial Tea Court. It's beautiful.

3 Haiku

Sitting warm and dry

reading under umbrella

poolside summer rain

Geese alight on pond

Confusion of Wings and Waves

A sudden stillness

Thunder. Pouring rain.

A single lighted window,

the meeting drags on.

reading under umbrella

poolside summer rain

Geese alight on pond

Confusion of Wings and Waves

A sudden stillness

Thunder. Pouring rain.

A single lighted window,

the meeting drags on.

Books on Strategy

I've been asked the question, "how do I learn strategy." Before I answer, the next question might be “why learn strategy?” The answer is simple. At the very least so you can recognize when someone is trying to manipulate you, or events to your disadvantage.

Here is my recommendation:

Mark McNeilly's books on Sun Tzu are an excellent, (IMO) introduction to the subject. I suggest starting by reading one of them. I think the one on Sun Tzu and Business, is easier to grasp because business dealings are closer to most of us than warfare.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0195137892/qid=1120137071/sr=2-1/ref=pd_bbs_b_2_1/103-7411287-7955859

McNeilly breaks ST down to six principles, which is a tool to embrace the topic.

Then I would recommend reading any of the fine translations that are available. In fact, I would suggest, over time acquiring several different translations, and not being shy about making notes and annotations in margins. Ralph Sawyer’s translation is especially good.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/1586635603/qid=1120137128/sr=8-1/ref=sr_8_xs_ap_i1_xgl14/103-7411287-7955859?v=glance&s=books&n=507846

At this point, one has a overview of the topic. Now it's time to see some applications. At this point I would introduce The 48 Laws of Power, and the 36 Strategies.

What I like about the 48 laws book is two things: it overlaps Sun Tzu, the 36 strategies, Machiavelli, East and West, modern and ancient; you name it - and each law is thoroughly explored and illustrated with numerous examples from history and literature. There are counter examples as well. It is a very well put together book.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0140280197/qid=1120137300/sr=8-1/ref=pd_bbs_1/103-7411287-7955859?v=glance&s=books&n=507846

A fairly new translation of the 36 strategies is called The Art of the Advantage. It is another very well done book.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/1587991683/qid=1120137383/sr=8-1/ref=pd_bbs_1/103-7411287-7955859?v=glance&s=books&n=507846

After studying these books, one should get an idea of how strategy is applied.

I drill myself, by looking at the events that unfold around me, and try to identify the specific law or strategy that is being used. I begin first by being able to identify them, then apply them.

I believe that a would be strategist could learn a lot from improving his chess (or go) game, and playing poker. These games use a lot of strategy, but different aspects.

I would also suggest becoming a student of a sport. I like hockey. Watch the strategies that the teams are using to win; the strategies that the owners and players are using on each other; the strategies that the teams' marketing organizations are using on the fans. Think of it as an ongoing case study.

After establishing a core library - branch out. Other favorites of mine are The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and the Book of Five Rings. Don't stop with just pure "strategy" books. Read widely and think about what you've read. Classics, science fiction, thrillers, every genre. Wisdom can be found nearly anywhere if you care to look.

Musashi urges the strategist to be acquainted with all things. The more you know about many things, the more creative you'll be. To succeed as a strategist, you should strive to be a polymath.

Becoming a strategist has been key to my job in marketing. Strategy applies to all aspects of your life. It's all about moving pieces around on a board. It's not enough to just read about strategy, but being able to apply it.

Thanks for your time.

Best Regards,

Rick

Here is my recommendation:

Mark McNeilly's books on Sun Tzu are an excellent, (IMO) introduction to the subject. I suggest starting by reading one of them. I think the one on Sun Tzu and Business, is easier to grasp because business dealings are closer to most of us than warfare.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0195137892/qid=1120137071/sr=2-1/ref=pd_bbs_b_2_1/103-7411287-7955859

McNeilly breaks ST down to six principles, which is a tool to embrace the topic.

Then I would recommend reading any of the fine translations that are available. In fact, I would suggest, over time acquiring several different translations, and not being shy about making notes and annotations in margins. Ralph Sawyer’s translation is especially good.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/1586635603/qid=1120137128/sr=8-1/ref=sr_8_xs_ap_i1_xgl14/103-7411287-7955859?v=glance&s=books&n=507846

At this point, one has a overview of the topic. Now it's time to see some applications. At this point I would introduce The 48 Laws of Power, and the 36 Strategies.

What I like about the 48 laws book is two things: it overlaps Sun Tzu, the 36 strategies, Machiavelli, East and West, modern and ancient; you name it - and each law is thoroughly explored and illustrated with numerous examples from history and literature. There are counter examples as well. It is a very well put together book.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0140280197/qid=1120137300/sr=8-1/ref=pd_bbs_1/103-7411287-7955859?v=glance&s=books&n=507846

A fairly new translation of the 36 strategies is called The Art of the Advantage. It is another very well done book.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/1587991683/qid=1120137383/sr=8-1/ref=pd_bbs_1/103-7411287-7955859?v=glance&s=books&n=507846

After studying these books, one should get an idea of how strategy is applied.

I drill myself, by looking at the events that unfold around me, and try to identify the specific law or strategy that is being used. I begin first by being able to identify them, then apply them.

I believe that a would be strategist could learn a lot from improving his chess (or go) game, and playing poker. These games use a lot of strategy, but different aspects.

I would also suggest becoming a student of a sport. I like hockey. Watch the strategies that the teams are using to win; the strategies that the owners and players are using on each other; the strategies that the teams' marketing organizations are using on the fans. Think of it as an ongoing case study.

After establishing a core library - branch out. Other favorites of mine are The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and the Book of Five Rings. Don't stop with just pure "strategy" books. Read widely and think about what you've read. Classics, science fiction, thrillers, every genre. Wisdom can be found nearly anywhere if you care to look.

Musashi urges the strategist to be acquainted with all things. The more you know about many things, the more creative you'll be. To succeed as a strategist, you should strive to be a polymath.

Becoming a strategist has been key to my job in marketing. Strategy applies to all aspects of your life. It's all about moving pieces around on a board. It's not enough to just read about strategy, but being able to apply it.

Thanks for your time.

Best Regards,

Rick

Wednesday, June 29, 2005

The Boat

If a man is crossing a river

And an empty boat collides With his own skiff,

Even though he be a bad-tempered man

He will not become very angry.

But if he sees a man in the boat,

He will shout at him to steer clear.

If the shout is not heard, he will shout again,

And yet again, and begin cursing.

And all because there is somebody in the boat.

Yet if the boat were empty,

He would not be shouting, and not angry.

If you can empty your own boat

Crossing the river of the world,

No one will oppose you,

No one will seek to harm you.

Zhuang Zi

And an empty boat collides With his own skiff,

Even though he be a bad-tempered man

He will not become very angry.

But if he sees a man in the boat,

He will shout at him to steer clear.

If the shout is not heard, he will shout again,

And yet again, and begin cursing.

And all because there is somebody in the boat.

Yet if the boat were empty,

He would not be shouting, and not angry.

If you can empty your own boat

Crossing the river of the world,

No one will oppose you,

No one will seek to harm you.

Zhuang Zi

Shut Up and Sit Down: Zen Books

If you click on the title of this post, you'll be directed to the webstie for Brad Warner, author of Hardcore Zen. Warner is a regular working guy with a wife and kids, and a job. He used to play bass in a punk band years ago, and is an ordained Zen priest.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/086171380X/qid=1120055808/sr=2-1/ref=pd_bbs_b_2_1/103-7411287-7955859

I am impressed by his no nonsense, take no prisoners approach to explaining his views on Zen. He doesn't need to go by some Asian sounding name to appear more "authentic."

His website is loaded with articles about Zen practice, and criticism of what passes for Zen.

Another author who is worth checking out is Charlotte Joko Beck. She's a little older and gentler than Warner in her writing, but to me she's saying essentially the same things. She wrote two books.

Everyday Zen: Love and Work

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0060607343/ref=pd_ecc_rvi_3/103-7411287-7955859?%5Fencoding=UTF8&v=glance

and Nothing Special: Living Zen

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0062511173/ref=pd_ecc_rvi_3/103-7411287-7955859?%5Fencoding=UTF8&v=glance

Finally, there is the gentlest voice of all, Shunryu Suzuki in his classic, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0834800799/ref=pd_ecc_rvi_3/103-7411287-7955859?%5Fencoding=UTF8&v=glance

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/086171380X/qid=1120055808/sr=2-1/ref=pd_bbs_b_2_1/103-7411287-7955859

I am impressed by his no nonsense, take no prisoners approach to explaining his views on Zen. He doesn't need to go by some Asian sounding name to appear more "authentic."

His website is loaded with articles about Zen practice, and criticism of what passes for Zen.

Another author who is worth checking out is Charlotte Joko Beck. She's a little older and gentler than Warner in her writing, but to me she's saying essentially the same things. She wrote two books.

Everyday Zen: Love and Work

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0060607343/ref=pd_ecc_rvi_3/103-7411287-7955859?%5Fencoding=UTF8&v=glance

and Nothing Special: Living Zen

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0062511173/ref=pd_ecc_rvi_3/103-7411287-7955859?%5Fencoding=UTF8&v=glance

Finally, there is the gentlest voice of all, Shunryu Suzuki in his classic, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0834800799/ref=pd_ecc_rvi_3/103-7411287-7955859?%5Fencoding=UTF8&v=glance

Tuesday, June 28, 2005

300 Tang Dynasty Poems

The Tang Dynasty is widely thought of as a Golden age of poetry in China. Every homecoming or leavetaking, a birthday, any event was significant enough to demand a poem be composed.

The 300 poems is a famous anthology of some of the best poetry of that Golden Age.

If you click on the title of this post, you'll be taken to an on line version of the collection.

Enjoy.

The 300 poems is a famous anthology of some of the best poetry of that Golden Age.

If you click on the title of this post, you'll be taken to an on line version of the collection.

Enjoy.

Chen Taiji Master Chen Xiao Wang Seminar

Chen Taiji Master Chen Xiao Wang will be holding a seminar in Plymouth Michigan, from August 16 through the 21st. If you click on the title of this post, you will be directed to more seminar information.

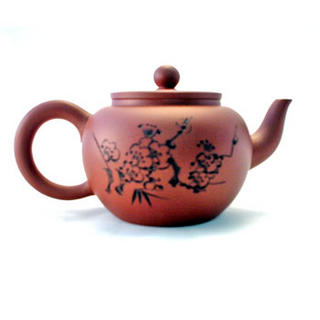

I am a little teapot ...

Monday, June 27, 2005

Wu Ming

A long time ago, before there were blogs, on line communities existed by means of mailing lists. One of these was a list called Tao-l. The topic was Taoism, and I still have fond memories of the banter and poetry that enlivened that community.

There was a phase when members began signing their posts with Taoist sounding names. As I couldn't think of one, I started signing my posts with whatever came to mind. During the autumn of one year, I became "The Leaf Raking Taoist." At another time, I figuratively threw up my hands and signed, "The No Name Taoist."

It was just after that a good friend sent me the following, and bestowed upon me the name of Wu Ming (No name). It's a story that I've always enjoyed.

Please visit the website I copied it from by clicking on the title of this post. First, I think it would simply be good manners; and second, that website has all sorts of interesting material on it.

Wu Ming - the No Name Taoist. Enjoy.

The Cucumber Sage:

The record of the life and teachings of Wu-Ming

As told by Master Tung-WangAbbott of Han-hsin monastery in theThirteenth year of the Earth Dragon period (898)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

My dear friend, the most reverend master Tung-Wang, Old and ill, I lay here knowing that writing this note will be my last act upon this earth and that by the time you read it I will be gone from this life.

Though we have not seen each other in the many years since we studied together under our most venerable Master, I have often thought of you, his most worthy successor. Monks from throughout China say that you are a true lion of the Buddha Dharma; one whose eye is a shooting star, whose hands snatch lightning, and whose voice booms like thunder. It is said that your every action shakes heaven and earth and causes the elephants and dragons of delusion to scatter helplessly. I am told that your monastery is unrivaled in severity, and that under your exacting guidance hundreds of monks pursue their training with utmost zeal and vigor. I've also heard that in the enlightened successor department your luck has not been so good. Which brings me to the point of this letter.

I ask that you now draw your attention to the young man to whom this note is attached. As he stands before you, no doubt smiling stupidly as he stuffs himself with pickled cucumbers, you may be wondering if he is as complete a fool as he appears, and if so, what prompted me to send him to you. In answer to the first question, I assure you that Wu-Ming's foolishness is far more complete than mere appearance would lead you to believe. As for the second question, I can only say that despite so benumbed a condition, or perhaps because of it, still more likely, despite of and because of it, Wu-Ming seems to unwittingly and accidentally serve the function of a great Bodhisattva. Perhaps he can be of service to you.

Allow him sixteen hours of sleep daily and provide him with lots of pickled cucumbers and Wu-Ming will always be happy. Expect nothing of him and you will be happy.

Respectfully, Chin-Mang

After Chin-mang's funeral, the supporters of his temple arranged for Wu-Ming's journey to Han-hsin monastery, where I resided, then, as now, as Abbott. A monk found Wu-ming at the monastery gate and seeing a note bearing my name pinned to his robe, led him to my quarters.

Customarily, when first presenting himself to the Abbott, a newly arrived monk will prostrate himself three times and ask respectfully to be accepted as a student. And so I was taken somewhat by surprise when Wu-ming walked into the room, took a pickled cucumber from the jar under his arm, stuffed it whole into his mouth, and happily munching away, broke into the toothless imbecilic grin that would one day become legendary. Taking a casual glance around the room, he smacked his lips loudly and said, "What's for lunch?"

After reading dear old Chin Mang's note, I called in the head monk and asked that he show my new student to the monk's quarters. When they had gone I reflected on chin-mang's words. Han-hsin was indeed a most severe place of training: winters were bitterly cold and in summer the sun blazed. The monks slept no more than three hours each night and ate one simple meal each day. For the remainder of the day they worked hard around the monastery and practiced hard in the meditation hall. But, alas, Chin-mang had heard correctly, Among all my disciples there was none whom I felt confident to be a worthy vessel to receive the untransmittable transmitted Dharma. I was beginning to despair that I would one day, bereft of even one successor, fail to fulfill my obligation of seeing my teacher's Dharma-linage continued.

The monks could hardly be faulted for complacency or indolence. Their sincere aspiration and disciplined effort were admirable indeed, and many had attained great clarity of wisdom. But they were preoccupied with their capacity for harsh discipline and proud of their insight. They squabbled with one another for positions of prestige and power and vied amongst themselves for recognition. Jealousy, rivalry and ambition seemed to hang like a dark cloud over Han-shin monastery, sucking even the most wise and sincere into its obscuring haze. Holding Chin-mang's note before me, I hoped and prayed that this Wu-ming, this "accidental Bodhisattva" might be the yeast my recipe seemed so much in need of.

To my astonished pleasure, Wu-ming took to life at Han-shin like a duck to water. At my request, he was assigned a job in the kitchen pickling vegetables. This he pursued tirelessly, and with a cheerful earnestness he gathered and mixed ingredients, lifted heavy barrels, drew and carried water, and, of course, freely sampled his workmanship. He was delighted!

When the monks assembled in the meditation hall, they would invariably find Wu-ming seated in utter stillness, apparently in deep and profound samadhi. No one even guessed that the only thing profound about Wu-ming's meditation was the profound unlikelihood that he might find the meditation posture, legs folded into the lotus position, back erect and centered, to be so wonderfully conducive to the long hours of sleep he so enjoyed.

Day after day and month after month, as the monks struggled to meet the physical and spiritual demands of monastery life, Wu-ming, with a grin and a whistle, sailed through it all effortlessly.

Even though, if the truth be told, Wu-ming's Zen practice was without the slightest merit, by way of outward appearance he was judged by all to be a monk of great accomplishment and perfect discipline. Of course . I could have dispelled this misconception easily enough, but I sensed that Wu-ming's unique brand of magic was taking effect and I was not about to throw away this most absurdly skillful of means.

By turns the monks were jealous, perplexed, hostile, humbled and inspired by what they presumed to be Wu-ming's great attainment. Of course it never occurred to Wu-ming that his or anyone else's behavior required such judgments, for they are the workings of a far more sophisticated nature than his own mind was capable. Indeed, everything about him was so obvious and simple that others thought him unfathomably subtle.

Wu-ming's inscrutable presence had a tremendously unsettling effect on the lives of the monks, and undercut the web of rationalizations that so often accompanies such upset. His utter obviousness rendered him unintelligible and immune to the social pretensions of others.

Attempts of flattery and invectives alike were met with the same uncomprehending grin, a grin the monks felt to be the very cutting edge of the sword of Perfect Wisdom. Finding no relief or diversion in such interchange, they were forced to seek out the source and resolution of their anguish each within his own mind. More importantly, and absurdly, Wu-ming caused to arise in the monks the unconquerable determination to fully penetrate the teaching "The Great Way is without difficulty" which they felt he embodied.

Though in the course of my lifetime I have encountered many of the most venerable progenitors of the Tathagata's teaching, never have I met one so skilled at awakening others to their intrinsic Buddhahood as this wonderful fool Wu-ming. His spiritual non-sequiturs were as sparks, lighting the flame of illuminating wisdom in the minds of many who engaged him in dialogue.

Once a monk approached Wu-ming and asked in all earnestness, "In the whole universe, what is it that is most wonderful?" Without hesitation Wu-ming stuck a cucumber before the monks face and exclaimed, "There is nothing more wonderful than this!" At that the monk crashed through the dualism of subject and object, "The whole universe is pickled cucumber; a pickled cucumber is the whole universe!" Wu-ming simply chuckled and said, "Stop talking nonsense. A cucumber is a cucumber; the whole universe is the whole universe. What could be more obvious?" The monk, penetrating the perfect phenomenal manifestation of Absolute Truth, clapped his hands and laughed, saying, "Throughout infinite space, everything is deliciously sour!"

On another occasion a monk asked Wu-ming, "The Third Patriarch said, "The Great Way is without difficulty, just cease having preferences." How can you then delight in eating cucumbers, yet refuse to even take one bit of a carrot?" Wu-ming said, "I love cucumbers; I hate carrots!"

The monk lurched back as though struck by a thunderbolt. Then laughing and sobbing and dancing about he exclaimed, "Liking cucumbers and hating carrots is without difficulty, just cease preferring the Great Way!"

Within three years of his arrival, the stories of the "Great Bodhisattva of Han-hsin monastery" had made their way throughout the provinces of China. Knowing of Wu-ming's fame I was not entirely surprised when a messenger from the Emperor appeared summoning Wu-ming to the Imperial Palace immediately.

From throughout the Empire exponents of the Three Teachings of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism were being called to the Capitol, there the Emperor would proclaim one to be the true religion to be practiced and preached in all lands under his rule. The idea of such competition for Imperial favor is not to my approval and the likelihood that a religious persecution might follow troubled me greatly. But an order from the Emperor is not to be ignored, so Wu-ming and I set out the next day.

Inside the Great Hall were gathered the more than one hundred priests and scholars who were to debate one another. They were surrounded by the most powerful lords in all China, along with innumerable advisors, of the Son of Heaven. All at once trumpets blared, cymbals crashed, and clouds of incense billowed up everywhere. The Emperor, borne on by a retinue of guards, was carried to the throne. After due formalities were observed the Emperor signaled for the debate to begin.

Several hours passed as one after another priests and scholars came forward presenting their doctrines and responding to questions. Through it all Wu-ming sat obliviously content as he stuffed himself with his favorite food. When his supply was finished, he happily crossed his legs, straightened his back and closed his eyes. But the noise and commotion were too great and, unable to sleep, he grew more restless and irritable by the minute. As I clasped him firmly by the back of the neck in an effort to restrain him, the Emperor gestured to Wu-ming to approach the Throne.

When Wu-ming had come before him, the Emperor said, "Throughout the land you are praised as a Bodhisattva whose mind is like the Great Void itself, yet you have not had a word to offer this assembly. Therefore I say to you now, teach me the True Way that all under heaven must follow." Wu-ming said nothing. After a few moments the Emperor, with a note of impatience, spoke again, "Perhaps you do not hear well so I shall repeat myself! Teach me the True Way that all under heaven must follow!" Still Wu-ming said nothing, and silence rippled through the crowd as all strained forward to witness this monk who dared behave so bold a fashion in the Emperor's presence.

Wu-ming heard nothing the Emperor said, nor did he notice the tension that vibrated through the hall. All that concerned him was his wish to find a nice quiet place where he could sleep undisturbed. The Emperor spoke again, his voice shaking with fury, his face flushed with anger: "You have been summoned to this council to speak on behalf of the Buddhist teaching. Your disrespect will not be tolerated much longer. I shall ask one more time, and should you fail to answer, I assure you the consequence shall be most grave. Teach me the True Way that all under heaven must follow!" Without a word Wu-ming turned and, as all looked on in dumbfounded silence, he made his way down the aisle and out the door. There was a hush of stunned disbelief before the crowd erupted into an uproar of confusion. Some were applauding Wu-ming's brilliant demonstration of religious insight, while others rushed about in an indignant rage, hurling threats and abuses at the doorway he had just passed through. Not knowing whether to praise Wu-ming or to have him beheaded, the Emperor turned to his advisors, but they were none the wiser. Finally, looking out at the frantic anarchy to which his grand debate had been reduced, the Emperor must surely have realized that no matter what Wu-ming's intentions might have been, there was now only one way to avoid the debate becoming a most serious embarrassment.

"The great sage of Han-hsin monastery has skillfully demonstrated that the great Tao cannot be confined by doctrines, but is best expounded through harmonious action. Let us profit by the wisdom he has so compassionately shared, and each endeavor to make our every step one that unites heaven and earth in accord with the profound and subtle Tao."

Having thus spoken the Son of Heaven concluded the Great Debate.

I immediately ran out to find Wu-ming, but he had disappeared in the crowded streets of the capitol.

Ten years have since passed, and I have seen nothing of him. However, on occasion a wandering monk will stop at Han-hsin with some bit of news. I am told that Wu-ming has been wandering about the countryside this past decade, trying unsuccessfully to find his way home. Because of his fame he is greeted and cared for in all quarters with generous kindness; however, those wishing to help him on his journey usually find that they have been helped on their own.

One young monk told of an encounter in which Wu-ming asked him, "Can you tell me where my home is?" Confused as to the spirit of the question. The monk replied, "Is the home you speak of to be found in the relative world of time and place, or do you mean the Original Home of all pervading Buddha nature?"

After pausing a moment to consider the question, Wu-ming looked up and, grinning as only he is capable, said, "Yes."

There was a phase when members began signing their posts with Taoist sounding names. As I couldn't think of one, I started signing my posts with whatever came to mind. During the autumn of one year, I became "The Leaf Raking Taoist." At another time, I figuratively threw up my hands and signed, "The No Name Taoist."

It was just after that a good friend sent me the following, and bestowed upon me the name of Wu Ming (No name). It's a story that I've always enjoyed.

Please visit the website I copied it from by clicking on the title of this post. First, I think it would simply be good manners; and second, that website has all sorts of interesting material on it.

Wu Ming - the No Name Taoist. Enjoy.

The Cucumber Sage:

The record of the life and teachings of Wu-Ming

As told by Master Tung-WangAbbott of Han-hsin monastery in theThirteenth year of the Earth Dragon period (898)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

My dear friend, the most reverend master Tung-Wang, Old and ill, I lay here knowing that writing this note will be my last act upon this earth and that by the time you read it I will be gone from this life.

Though we have not seen each other in the many years since we studied together under our most venerable Master, I have often thought of you, his most worthy successor. Monks from throughout China say that you are a true lion of the Buddha Dharma; one whose eye is a shooting star, whose hands snatch lightning, and whose voice booms like thunder. It is said that your every action shakes heaven and earth and causes the elephants and dragons of delusion to scatter helplessly. I am told that your monastery is unrivaled in severity, and that under your exacting guidance hundreds of monks pursue their training with utmost zeal and vigor. I've also heard that in the enlightened successor department your luck has not been so good. Which brings me to the point of this letter.

I ask that you now draw your attention to the young man to whom this note is attached. As he stands before you, no doubt smiling stupidly as he stuffs himself with pickled cucumbers, you may be wondering if he is as complete a fool as he appears, and if so, what prompted me to send him to you. In answer to the first question, I assure you that Wu-Ming's foolishness is far more complete than mere appearance would lead you to believe. As for the second question, I can only say that despite so benumbed a condition, or perhaps because of it, still more likely, despite of and because of it, Wu-Ming seems to unwittingly and accidentally serve the function of a great Bodhisattva. Perhaps he can be of service to you.

Allow him sixteen hours of sleep daily and provide him with lots of pickled cucumbers and Wu-Ming will always be happy. Expect nothing of him and you will be happy.

Respectfully, Chin-Mang

After Chin-mang's funeral, the supporters of his temple arranged for Wu-Ming's journey to Han-hsin monastery, where I resided, then, as now, as Abbott. A monk found Wu-ming at the monastery gate and seeing a note bearing my name pinned to his robe, led him to my quarters.

Customarily, when first presenting himself to the Abbott, a newly arrived monk will prostrate himself three times and ask respectfully to be accepted as a student. And so I was taken somewhat by surprise when Wu-ming walked into the room, took a pickled cucumber from the jar under his arm, stuffed it whole into his mouth, and happily munching away, broke into the toothless imbecilic grin that would one day become legendary. Taking a casual glance around the room, he smacked his lips loudly and said, "What's for lunch?"

After reading dear old Chin Mang's note, I called in the head monk and asked that he show my new student to the monk's quarters. When they had gone I reflected on chin-mang's words. Han-hsin was indeed a most severe place of training: winters were bitterly cold and in summer the sun blazed. The monks slept no more than three hours each night and ate one simple meal each day. For the remainder of the day they worked hard around the monastery and practiced hard in the meditation hall. But, alas, Chin-mang had heard correctly, Among all my disciples there was none whom I felt confident to be a worthy vessel to receive the untransmittable transmitted Dharma. I was beginning to despair that I would one day, bereft of even one successor, fail to fulfill my obligation of seeing my teacher's Dharma-linage continued.

The monks could hardly be faulted for complacency or indolence. Their sincere aspiration and disciplined effort were admirable indeed, and many had attained great clarity of wisdom. But they were preoccupied with their capacity for harsh discipline and proud of their insight. They squabbled with one another for positions of prestige and power and vied amongst themselves for recognition. Jealousy, rivalry and ambition seemed to hang like a dark cloud over Han-shin monastery, sucking even the most wise and sincere into its obscuring haze. Holding Chin-mang's note before me, I hoped and prayed that this Wu-ming, this "accidental Bodhisattva" might be the yeast my recipe seemed so much in need of.

To my astonished pleasure, Wu-ming took to life at Han-shin like a duck to water. At my request, he was assigned a job in the kitchen pickling vegetables. This he pursued tirelessly, and with a cheerful earnestness he gathered and mixed ingredients, lifted heavy barrels, drew and carried water, and, of course, freely sampled his workmanship. He was delighted!

When the monks assembled in the meditation hall, they would invariably find Wu-ming seated in utter stillness, apparently in deep and profound samadhi. No one even guessed that the only thing profound about Wu-ming's meditation was the profound unlikelihood that he might find the meditation posture, legs folded into the lotus position, back erect and centered, to be so wonderfully conducive to the long hours of sleep he so enjoyed.

Day after day and month after month, as the monks struggled to meet the physical and spiritual demands of monastery life, Wu-ming, with a grin and a whistle, sailed through it all effortlessly.

Even though, if the truth be told, Wu-ming's Zen practice was without the slightest merit, by way of outward appearance he was judged by all to be a monk of great accomplishment and perfect discipline. Of course . I could have dispelled this misconception easily enough, but I sensed that Wu-ming's unique brand of magic was taking effect and I was not about to throw away this most absurdly skillful of means.

By turns the monks were jealous, perplexed, hostile, humbled and inspired by what they presumed to be Wu-ming's great attainment. Of course it never occurred to Wu-ming that his or anyone else's behavior required such judgments, for they are the workings of a far more sophisticated nature than his own mind was capable. Indeed, everything about him was so obvious and simple that others thought him unfathomably subtle.

Wu-ming's inscrutable presence had a tremendously unsettling effect on the lives of the monks, and undercut the web of rationalizations that so often accompanies such upset. His utter obviousness rendered him unintelligible and immune to the social pretensions of others.

Attempts of flattery and invectives alike were met with the same uncomprehending grin, a grin the monks felt to be the very cutting edge of the sword of Perfect Wisdom. Finding no relief or diversion in such interchange, they were forced to seek out the source and resolution of their anguish each within his own mind. More importantly, and absurdly, Wu-ming caused to arise in the monks the unconquerable determination to fully penetrate the teaching "The Great Way is without difficulty" which they felt he embodied.

Though in the course of my lifetime I have encountered many of the most venerable progenitors of the Tathagata's teaching, never have I met one so skilled at awakening others to their intrinsic Buddhahood as this wonderful fool Wu-ming. His spiritual non-sequiturs were as sparks, lighting the flame of illuminating wisdom in the minds of many who engaged him in dialogue.

Once a monk approached Wu-ming and asked in all earnestness, "In the whole universe, what is it that is most wonderful?" Without hesitation Wu-ming stuck a cucumber before the monks face and exclaimed, "There is nothing more wonderful than this!" At that the monk crashed through the dualism of subject and object, "The whole universe is pickled cucumber; a pickled cucumber is the whole universe!" Wu-ming simply chuckled and said, "Stop talking nonsense. A cucumber is a cucumber; the whole universe is the whole universe. What could be more obvious?" The monk, penetrating the perfect phenomenal manifestation of Absolute Truth, clapped his hands and laughed, saying, "Throughout infinite space, everything is deliciously sour!"

On another occasion a monk asked Wu-ming, "The Third Patriarch said, "The Great Way is without difficulty, just cease having preferences." How can you then delight in eating cucumbers, yet refuse to even take one bit of a carrot?" Wu-ming said, "I love cucumbers; I hate carrots!"

The monk lurched back as though struck by a thunderbolt. Then laughing and sobbing and dancing about he exclaimed, "Liking cucumbers and hating carrots is without difficulty, just cease preferring the Great Way!"

Within three years of his arrival, the stories of the "Great Bodhisattva of Han-hsin monastery" had made their way throughout the provinces of China. Knowing of Wu-ming's fame I was not entirely surprised when a messenger from the Emperor appeared summoning Wu-ming to the Imperial Palace immediately.

From throughout the Empire exponents of the Three Teachings of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism were being called to the Capitol, there the Emperor would proclaim one to be the true religion to be practiced and preached in all lands under his rule. The idea of such competition for Imperial favor is not to my approval and the likelihood that a religious persecution might follow troubled me greatly. But an order from the Emperor is not to be ignored, so Wu-ming and I set out the next day.

Inside the Great Hall were gathered the more than one hundred priests and scholars who were to debate one another. They were surrounded by the most powerful lords in all China, along with innumerable advisors, of the Son of Heaven. All at once trumpets blared, cymbals crashed, and clouds of incense billowed up everywhere. The Emperor, borne on by a retinue of guards, was carried to the throne. After due formalities were observed the Emperor signaled for the debate to begin.

Several hours passed as one after another priests and scholars came forward presenting their doctrines and responding to questions. Through it all Wu-ming sat obliviously content as he stuffed himself with his favorite food. When his supply was finished, he happily crossed his legs, straightened his back and closed his eyes. But the noise and commotion were too great and, unable to sleep, he grew more restless and irritable by the minute. As I clasped him firmly by the back of the neck in an effort to restrain him, the Emperor gestured to Wu-ming to approach the Throne.

When Wu-ming had come before him, the Emperor said, "Throughout the land you are praised as a Bodhisattva whose mind is like the Great Void itself, yet you have not had a word to offer this assembly. Therefore I say to you now, teach me the True Way that all under heaven must follow." Wu-ming said nothing. After a few moments the Emperor, with a note of impatience, spoke again, "Perhaps you do not hear well so I shall repeat myself! Teach me the True Way that all under heaven must follow!" Still Wu-ming said nothing, and silence rippled through the crowd as all strained forward to witness this monk who dared behave so bold a fashion in the Emperor's presence.

Wu-ming heard nothing the Emperor said, nor did he notice the tension that vibrated through the hall. All that concerned him was his wish to find a nice quiet place where he could sleep undisturbed. The Emperor spoke again, his voice shaking with fury, his face flushed with anger: "You have been summoned to this council to speak on behalf of the Buddhist teaching. Your disrespect will not be tolerated much longer. I shall ask one more time, and should you fail to answer, I assure you the consequence shall be most grave. Teach me the True Way that all under heaven must follow!" Without a word Wu-ming turned and, as all looked on in dumbfounded silence, he made his way down the aisle and out the door. There was a hush of stunned disbelief before the crowd erupted into an uproar of confusion. Some were applauding Wu-ming's brilliant demonstration of religious insight, while others rushed about in an indignant rage, hurling threats and abuses at the doorway he had just passed through. Not knowing whether to praise Wu-ming or to have him beheaded, the Emperor turned to his advisors, but they were none the wiser. Finally, looking out at the frantic anarchy to which his grand debate had been reduced, the Emperor must surely have realized that no matter what Wu-ming's intentions might have been, there was now only one way to avoid the debate becoming a most serious embarrassment.

"The great sage of Han-hsin monastery has skillfully demonstrated that the great Tao cannot be confined by doctrines, but is best expounded through harmonious action. Let us profit by the wisdom he has so compassionately shared, and each endeavor to make our every step one that unites heaven and earth in accord with the profound and subtle Tao."

Having thus spoken the Son of Heaven concluded the Great Debate.

I immediately ran out to find Wu-ming, but he had disappeared in the crowded streets of the capitol.

Ten years have since passed, and I have seen nothing of him. However, on occasion a wandering monk will stop at Han-hsin with some bit of news. I am told that Wu-ming has been wandering about the countryside this past decade, trying unsuccessfully to find his way home. Because of his fame he is greeted and cared for in all quarters with generous kindness; however, those wishing to help him on his journey usually find that they have been helped on their own.

One young monk told of an encounter in which Wu-ming asked him, "Can you tell me where my home is?" Confused as to the spirit of the question. The monk replied, "Is the home you speak of to be found in the relative world of time and place, or do you mean the Original Home of all pervading Buddha nature?"

After pausing a moment to consider the question, Wu-ming looked up and, grinning as only he is capable, said, "Yes."

Sunday, June 26, 2005

Freshly Cut Grass

A cold beer never tastes quite as good as it does just after the lawn has been cut.

Having cut the lawn,

A cold beer beckons to me.

Watching. Drinking. Rain.

Having cut the lawn,

A cold beer beckons to me.

Watching. Drinking. Rain.

Tombstone and One Thing Leads to Another

The movie Tombstone, starring Kurt Russel and Val Kilmer, was on cable last night. A great modern western. It was well written, directed, and acted, especially by Russel and Kilmer.

Personally, I think Kilmer stole the show as Doc Holiday.

This got me to thinking about how a number of good Kurt Russel movies had been on cable in the last few months: Wild Bill, Soldier (great line : "I'll kill them all, sir."), Big Trouble in Little China ("I'm feeling very confident!" and a young Kim Catrall!), Escape from NY ( I think I saw some of the extras at the 7-11 the other day), and Escape from LA (Snake Plisken is a great character).

I can't remember a lot of Val Kilmer films. The Doors and The Saint come readily to mind. His co-star in The Saint was Elizabeth Shue.

Shue has quite a range. In one weekend, I saw a young Shue in Adventures in Babysitting, and Palmetto, where she was a smoldering sex pot.

Another actress who had shown quite a range is Winona Ryder. Again, in one weekend, I saw her in Little Women, and in Dracula.

Personally, I think Kilmer stole the show as Doc Holiday.

This got me to thinking about how a number of good Kurt Russel movies had been on cable in the last few months: Wild Bill, Soldier (great line : "I'll kill them all, sir."), Big Trouble in Little China ("I'm feeling very confident!" and a young Kim Catrall!), Escape from NY ( I think I saw some of the extras at the 7-11 the other day), and Escape from LA (Snake Plisken is a great character).

I can't remember a lot of Val Kilmer films. The Doors and The Saint come readily to mind. His co-star in The Saint was Elizabeth Shue.

Shue has quite a range. In one weekend, I saw a young Shue in Adventures in Babysitting, and Palmetto, where she was a smoldering sex pot.

Another actress who had shown quite a range is Winona Ryder. Again, in one weekend, I saw her in Little Women, and in Dracula.

Saturday, June 25, 2005

Cook Ding

Prince Huei's cook was cutting up a bullock. Every blow of his hand, every heave of his shoulders, every tread of his foot, every thrust of his knee, every whshh of rent flesh, every clink of the chopper, was in perfect rhythm — like the dance of the Mulberry Grove, like the harmonious chords of Ching Shou.

"Well done!" cried the Prince. "Yours is skill indeed!"

"Sire," replied the cook laying down his chopper, "I have always devoted myself to Tao, which is higher than mere skill. When I first began to cut up bullocks, I saw before me whole bullocks. After three years' practice, I saw no more whole animals. And now I work with my mind and not with my eye. My mind works along without the control of the senses. Falling back upon eternal principles, I glide through such great joints or cavities as there may be, according to the natural constitution of the animal. I do not even touch the convolutions of muscle and tendon, still less attempt to cut through large bones.

"A good cook changes his chopper once a year — because he cuts. An ordinary cook, one a month — because he hacks. But I have had this chopper nineteen years, and although I have cut up many thousand bullocks, its edge is as if fresh from the whetstone. For at the joints there are always interstices, and the edge of a chopper being without thickness, it remains only to insert that which is without thickness into such an interstice. Indeed there is plenty of room for the blade to move about. It is thus that I have kept my chopper for nineteen years as though fresh from the whetstone.

"Nevertheless, when I come upon a knotty part which is difficult to tackle, I am all caution. Fixing my eye on it, I stay my hand, and gently apply my blade, until with a hwah the part yields like earth crumbling to the ground. Then I take out my chopper and stand up, and look around, and pause with an air of triumph. Then wiping my chopper, I put it carefully away."

"Bravo!" cried the Prince. "From the words of this cook I have learned how to take care of my life."

ZhuangZi (Lin YuTang)

"Well done!" cried the Prince. "Yours is skill indeed!"

"Sire," replied the cook laying down his chopper, "I have always devoted myself to Tao, which is higher than mere skill. When I first began to cut up bullocks, I saw before me whole bullocks. After three years' practice, I saw no more whole animals. And now I work with my mind and not with my eye. My mind works along without the control of the senses. Falling back upon eternal principles, I glide through such great joints or cavities as there may be, according to the natural constitution of the animal. I do not even touch the convolutions of muscle and tendon, still less attempt to cut through large bones.

"A good cook changes his chopper once a year — because he cuts. An ordinary cook, one a month — because he hacks. But I have had this chopper nineteen years, and although I have cut up many thousand bullocks, its edge is as if fresh from the whetstone. For at the joints there are always interstices, and the edge of a chopper being without thickness, it remains only to insert that which is without thickness into such an interstice. Indeed there is plenty of room for the blade to move about. It is thus that I have kept my chopper for nineteen years as though fresh from the whetstone.

"Nevertheless, when I come upon a knotty part which is difficult to tackle, I am all caution. Fixing my eye on it, I stay my hand, and gently apply my blade, until with a hwah the part yields like earth crumbling to the ground. Then I take out my chopper and stand up, and look around, and pause with an air of triumph. Then wiping my chopper, I put it carefully away."

"Bravo!" cried the Prince. "From the words of this cook I have learned how to take care of my life."

ZhuangZi (Lin YuTang)

Retirement planning

I’m in my late 40’s, and it appears that I’ll have at least another 15, but with hope, not more than 20 years more to work. Much like everyone else my age, retirement planning is taking more and more importance in my view of things.

One item that I think a lot of people don’t think much about, and leave to chance is the question of what will be their “retirement job.” I want to get a notion of what I could do in retirement that I might be able to get a start on much earlier to see if I like it, and get good enough at it that I might be able to make a little money, which is the ultimate goal.

I know some guys who could finish basements or build decks, but I don’t have those skills or really the interest. Working in a bookstore sounds interesting, but the main skill required in a bookstore is the ability to lift heavy boxes of books; and besides, I’ve worked in retail before, and I don’t really want to do that again.

I don’t even want to think about ending up at a McDonald’s or a Home Depot.

Without any immediate answers, I resolved to let the question stand, revisit it from time to time, and turn it over from as many different viewpoints as I could.

Last New Year, I took a job with a new company. I am now working for a large Japanese corporation. Something I noticed was that the translations of our technical documentation was in pretty rough shape. They are either done by software in Japan and shipped over here to be proofread, or translated one of two people with whom I work (neither a native English speaker).

I’ve always been interested in Chinese and Japanese things, especially martial arts and philosophy. I decided to make an opportunity for myself to learn Japanese. If I could get my fingers into some of the translation work, I’ll have secured another hook into my long term viability with the company (with things being what they are these days, we don’t want to take our job security for granted). Also, being able to communicate with the Japanese in my company well in their own language could only help me.

To tie this back into retirement planning, with 15 to 20 years to polish my Japanese language skills, having a technical marketing background, and certainly being in the right place to learn the technical jargon, I can see myself as some sort of business consultant and free lance translator.

It may not be perfect, but it’s a plan, and I’ve been following it. I’m almost through the first of five “levels” of lessons at www.YesJapan.com.

Right now, I have a basic grammar, a growing vocabulary, and can read hiragana, one of the four types of writing used in Japan. I’m about to start on katagana. I’m also about to subscribe to a bilingual Japanese magazine to put my study to work, making me apply what I’ve learned, which will make it stick.

If nothing else, I will have learned something interesting.

One item that I think a lot of people don’t think much about, and leave to chance is the question of what will be their “retirement job.” I want to get a notion of what I could do in retirement that I might be able to get a start on much earlier to see if I like it, and get good enough at it that I might be able to make a little money, which is the ultimate goal.

I know some guys who could finish basements or build decks, but I don’t have those skills or really the interest. Working in a bookstore sounds interesting, but the main skill required in a bookstore is the ability to lift heavy boxes of books; and besides, I’ve worked in retail before, and I don’t really want to do that again.

I don’t even want to think about ending up at a McDonald’s or a Home Depot.

Without any immediate answers, I resolved to let the question stand, revisit it from time to time, and turn it over from as many different viewpoints as I could.

Last New Year, I took a job with a new company. I am now working for a large Japanese corporation. Something I noticed was that the translations of our technical documentation was in pretty rough shape. They are either done by software in Japan and shipped over here to be proofread, or translated one of two people with whom I work (neither a native English speaker).

I’ve always been interested in Chinese and Japanese things, especially martial arts and philosophy. I decided to make an opportunity for myself to learn Japanese. If I could get my fingers into some of the translation work, I’ll have secured another hook into my long term viability with the company (with things being what they are these days, we don’t want to take our job security for granted). Also, being able to communicate with the Japanese in my company well in their own language could only help me.

To tie this back into retirement planning, with 15 to 20 years to polish my Japanese language skills, having a technical marketing background, and certainly being in the right place to learn the technical jargon, I can see myself as some sort of business consultant and free lance translator.

It may not be perfect, but it’s a plan, and I’ve been following it. I’m almost through the first of five “levels” of lessons at www.YesJapan.com.

Right now, I have a basic grammar, a growing vocabulary, and can read hiragana, one of the four types of writing used in Japan. I’m about to start on katagana. I’m also about to subscribe to a bilingual Japanese magazine to put my study to work, making me apply what I’ve learned, which will make it stick.

If nothing else, I will have learned something interesting.

Would you like a cup of tea?

"Meanwhile, let us have a sip of tea. The afternoon glow is brightening the bamboos, the fountains are bubbling with delight, the soughing of the pines is heard in our kettle. Let us dream of evanescence, and linger in the beautiful foolishness of things."

Okakura Kakuzo Book of Tea (1906)

All my life, I had been a coffee drinker. I’d drink it by the pots, if not by the urns. I’d have an occasional cup of tea once in a while. Maybe iced tea on a hot day, but I was never really a tea drinker.

A couple of years ago, I caught a terrible flu. I lost close to 15 lbs. I also largely broke the habit of drinking coffee. While I was sick, it was really unappealing to me, and I simply got out of the habit of drinking so much of it. I came around to liking the taste of tea.

It was around that same time, when I was developing a taste for tea, that some martial arts friends of mine had turned to tea, and I was exposed to some good teas, as opposed to the ubiquitous Lipton Brisk, which is a barely digestible mixture of some red and black teas.

I’ve tasted some various teas, and developed some taste. I still drink coffee first thing in the morning to get me going, but the morning tea I like the best is Oolong. It goes well with a bagel. It has a heavier taste, in the direction of coffee, but not so extreme. The aroma is pleasing too.

In the afternoon, I like a nice green tea. Green tea has a very clean taste. After lunch, I feel that a cup of green tea cleanses any aftertaste from whatever I’ve eaten. I still have the caffeine effect in that it helps me stay alert in the afternoon, but without the coffee jitters.

I’m continuing to learn more, try different teas, and just follow my tastes.

A book on tea for beginners, that is really beautifully laid out is The Way of Tea by Lam Kam Chuen ( http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0764119680/ref=pd_sxp_f/103-7411287-7955859?v=glance&s=books ) .

For very good tea, accessories, etc, try www.ImperialTea.com

Okakura Kakuzo Book of Tea (1906)

All my life, I had been a coffee drinker. I’d drink it by the pots, if not by the urns. I’d have an occasional cup of tea once in a while. Maybe iced tea on a hot day, but I was never really a tea drinker.

A couple of years ago, I caught a terrible flu. I lost close to 15 lbs. I also largely broke the habit of drinking coffee. While I was sick, it was really unappealing to me, and I simply got out of the habit of drinking so much of it. I came around to liking the taste of tea.

It was around that same time, when I was developing a taste for tea, that some martial arts friends of mine had turned to tea, and I was exposed to some good teas, as opposed to the ubiquitous Lipton Brisk, which is a barely digestible mixture of some red and black teas.

I’ve tasted some various teas, and developed some taste. I still drink coffee first thing in the morning to get me going, but the morning tea I like the best is Oolong. It goes well with a bagel. It has a heavier taste, in the direction of coffee, but not so extreme. The aroma is pleasing too.

In the afternoon, I like a nice green tea. Green tea has a very clean taste. After lunch, I feel that a cup of green tea cleanses any aftertaste from whatever I’ve eaten. I still have the caffeine effect in that it helps me stay alert in the afternoon, but without the coffee jitters.

I’m continuing to learn more, try different teas, and just follow my tastes.

A book on tea for beginners, that is really beautifully laid out is The Way of Tea by Lam Kam Chuen ( http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0764119680/ref=pd_sxp_f/103-7411287-7955859?v=glance&s=books ) .

For very good tea, accessories, etc, try www.ImperialTea.com

It's hot outside

It’s about 400 degrees outside, and the humidity is around 10,000 %. Naturally, one’s thoughts turn to winter, when the wind chill is –60F, and gale force winds are trying to rip the frozen flesh right off of your bones.

Luckily, winter gives way to spring (which lasts about 15 minutes in Michigan, we tend to plunge directly back into summer). There is a time when it’s not quite winter, and not quite spring either …

Winter Cinquain

Of green

dreams in winter,

thawed brooks purl anew.

Phantom sunflowers touch the sky.

Waking.

Luckily, winter gives way to spring (which lasts about 15 minutes in Michigan, we tend to plunge directly back into summer). There is a time when it’s not quite winter, and not quite spring either …

Winter Cinquain

Of green

dreams in winter,

thawed brooks purl anew.

Phantom sunflowers touch the sky.

Waking.

Books and Movies

I think pretty much everyone is in agreement that when you have a movie made from a book, the book is generally better.

From time to time, you find a movie that stands well on it’s own, which is just as good as the book. The Godfather comes to mind. It was a great book, and also a great movie. Both works can stand on their own and don’t really need to be compared. Most of the many productions of A Christmas Carol fits this category as well.

It is more rare that a movie surpasses the book. Field of Dreams comes to mind. If you like the Forrest Gump movie, you’d be advised to leave the book alone. Eddie and the Cruisers, the movie, leaves the book in the dust.

Most recently, the Bourne Identity and Bourne Supremacy have come to the screen. I liked them, and decided that I was going to read the Bournce Trilogy by Robert Ludlum. The books were truly awful.

Ludlum comes up with some really intriguing ideas, such as this highly trained special agent with memory loss, but fails to execute. His characters are wooden, the dialog is terrible, he doesn’t know when to end a story. I continued to read just to see how bad it could get.

I wonder what a good writer, like John LeCarre (Smiley’s People) could have done with those ideas.

From time to time, you find a movie that stands well on it’s own, which is just as good as the book. The Godfather comes to mind. It was a great book, and also a great movie. Both works can stand on their own and don’t really need to be compared. Most of the many productions of A Christmas Carol fits this category as well.

It is more rare that a movie surpasses the book. Field of Dreams comes to mind. If you like the Forrest Gump movie, you’d be advised to leave the book alone. Eddie and the Cruisers, the movie, leaves the book in the dust.

Most recently, the Bourne Identity and Bourne Supremacy have come to the screen. I liked them, and decided that I was going to read the Bournce Trilogy by Robert Ludlum. The books were truly awful.

Ludlum comes up with some really intriguing ideas, such as this highly trained special agent with memory loss, but fails to execute. His characters are wooden, the dialog is terrible, he doesn’t know when to end a story. I continued to read just to see how bad it could get.

I wonder what a good writer, like John LeCarre (Smiley’s People) could have done with those ideas.

Basho's Frog

In his famous haiku, Basho wrote:

The old pond,A frog jumps in:Plop!

I wrote:

Basho's frog went plop!

and never heard from again.

A snapping turtle.

The old pond,A frog jumps in:Plop!

I wrote:

Basho's frog went plop!

and never heard from again.

A snapping turtle.